"The road from the avantgarde's experiments to

contemporary women's art seems to have been shorter,

less torturous, and ultimately more productive than the

less frequently traveled road from high modernism."

Thus "painting" is privileged in modernist discourse as the most ambitious and significant art form because of its combination of gesture and trace which secure by metonymy the presence of the artist. These inscribe a subjectivity whose value is, by visual inference and cultural naming, masculinity.

The arrival of pop art was the first sign of change in the art world. Pop art was no more receptive to women than was high modernism; it was the opposite of modernism--too cool, commercial, and composed for an emotive woman to be involved in. However, pop art provided some artistic expression other than modernism and opened up the art world to more pluralistic attitudes. Also by the end of the sixties, the Civil Rights and Women's Movements were underway; all of the outsider voices which had been so neatly repressed in the fifties began to emerge in the sixties. And from this discourse of difference sprang the feminist art movement.

The feminist artists of the late sixties and early seventies were faced with centuries of objectified female nudes as well as the misogynist expressionism of modernism. Not wanting to be silent participants in this tradition as perhaps Lee Krasner or Elaine de Kooning were, the seventies artists chose to work against these painterly traditions. These artists often made use of alternative media (performance art, book art, video art, etc.) to get their messages across.

During this period of artistic exploration and explosive politics, a number of women (previously in fields as varied as architecture and sculpture) began working with the new technology of video. The post-war frenzy for a televised culture and the development of cheaper, user-friendly recording equipment contributed to the creation of the new genre of video art. Of course, women were not alone on this technological frontier; many of the most well-known video art pioneers are men--Nam June Paik, Vito Acconci, and Bruce Nauman, to name only a few; but for the first time in the exploration of a new medium the men were not alone. In fact, as critic Jean Rasenberger points out, "By and large, a kind of egalitarian air enveloped the medium in the early seventies, and as a friend recently reminded me, video was one of the only mediums in which women began on equal footing with men."

Although men and women co-founded the genre of video art, their artistic aims and purposes were often quite different. For the most part, though not exclusively, men moved into the field of video with an interest in modernism and minimalism; they were interested in exploring the inherent qualities of the medium of video itself. Many women, of course, were also interested in these formalist aspects of the art form. However, in the era of the women's movement when every feminist had a button or bumpersticker proclaiming, "the personal is political", women video artists brought the personal and political into their work as well.

One of the most important aspects of feminism for many women artists was the exploration into the category of woman: sex vs. gender, biological vs. societal, essential vs. constructed, etc. Not only did the women working with video art have centuries of art history in which women had been objectified to deal with, but they had a whole new arena of patriarchy to consider--popular culture. An important early video artist, Dara Birnbaum, discusses her use of television footage in her work, and she points to the desire to incorporate the vernacular. "Film for me wasn't the current popular vocabulary, it was television. The Nielson ratings said that the average American family watched seven hours and twenty minutes a day." Birnbaum along with many other women in the field realized video's connection to broadcast television and used video to comment on and deconstruct the image of women in our televised culture. By concentrating on three early works--Martha Rosler's Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Joan Jonas's Vertical Roll (1971), and Dara Birnbaum's Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-79)--we will see how women used the medium of video art to question the accepted roles of women and the medium's place in the construction of those roles. Finally, we will conclude by looking toward television itself, particularly MTV, and the internet as the sites in which these early explorations are being continued today.

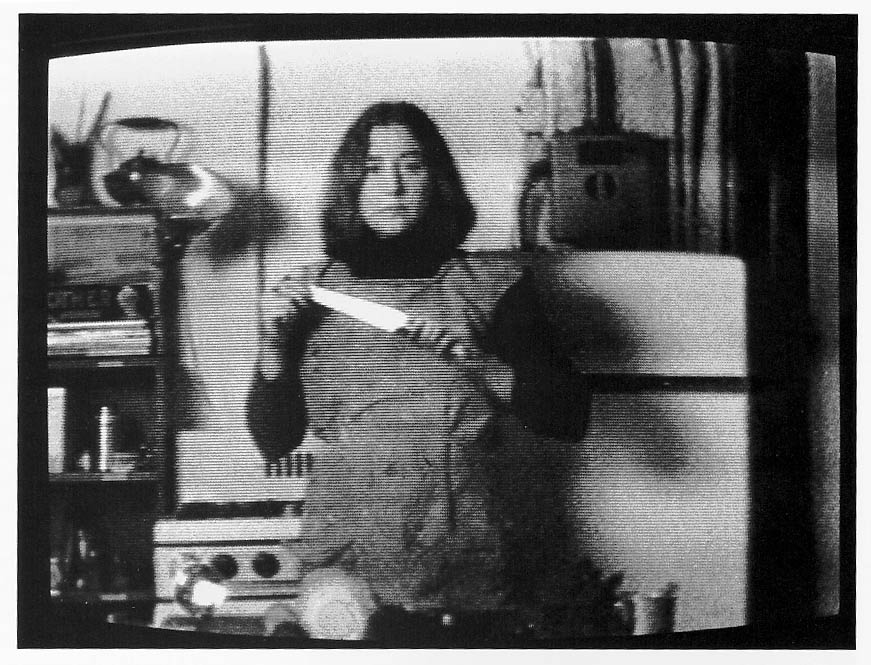

In her six minute, black and white video, Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Martha Rosler tackles the engendered space of the kitchen. In her own words, Rosler explains that in the piece an "anti-Julia Child replaces the domesticated 'meaning' of tools with a lexicon of rage and frustration." The work begins with Rosler standing behind a counter in a typical suburban kitchen; she holds up a chalkboard displaying the title and artist of the piece, and then proceeds to don her apron as if beginning the daily cooking show. But, rather than smile and introduce today's dish, Rosler begins her dead-pan skit. Beginning with apron, she continues naming kitchen objects in alphabetical order, displays them, and provides a brief demonstration including an action for each object .

We are not shown the expected actions; instead, Rosler provides us with a violent mixture of slamming and hitting. Including "fork", which she jabs into the air, and "icepick", which she stabs into the counter, the artist continues through the alphabet. After banging the "tenderizer" on the counter top, though, she runs out of objects and shows us "u" through "z" as would a cheerleader or airplane director. At the end of the alphabet Rosler folds her arms across her chest and in the last moment of the piece breaks from her robotic, emotionless, monotone display to quickly shrug.

The message of Semiotics is definitely not too hidden. Discussing Semiotics, artists L—pez and Roth state, "[S]he reveals with disarming humor the culinary arsenal available to women. An underlying motif is women's undeveloped power and suppressed rage." Rosler is not only pointing out that the woman who cooks you dinner every night may not be as content in the kitchen as she seems. By changing the typical action of the kitchen utensils to something strange and jarring and repeating the act of naming/demonstrating twenty times, Rosler points out the absurdity of the whole idea that a woman would find her "natural" place in the kitchen. Is the artist with her monotone voice and violent motions performing a scene of dead-pan irony? Or is the wife and mother who smilingly asks if you'd like seconds the one who is performing? In his essay on feminism and postmodernism, Craig Owens refers to the by-now common assertion that gender is performative; he writes, "[F]emininity is frequently associated with masquerade, with false representation, with simulation and seduction."

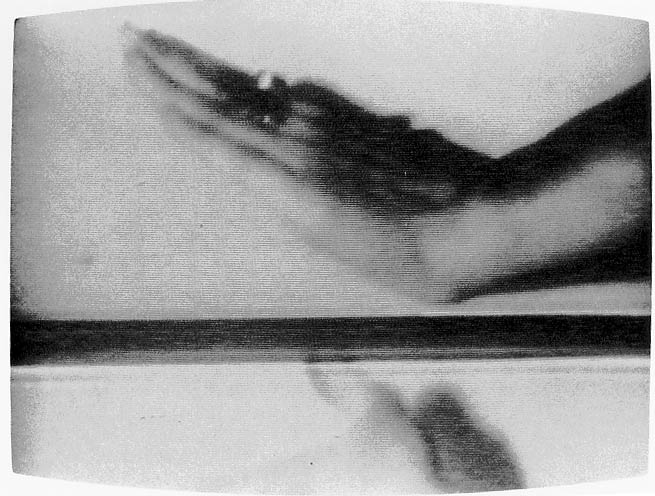

The themes of repetition and violence are carried over into the work of Joan Jonas. In her twenty minute, black and white video, Vertical Roll (1971), Jonas manipulates the medium to make the repetition and violence even more literal. The entire twenty minutes of action is accompanied by a loud clap synchronized to a horizontal bar dividing the image and rolling up the screen. This "vertical roll" can be see by misadjusting the v-hold on your television set and is the result of two out-of-sync frequencies--the signal sent to the monitor and the frequency by which it is interpreted.

The images which are cut up, reframed, and disrupted by the vertical roll include the artist performing a variety of acts. At times, Jonas plays with the repetitive sound and movement by marching to the beat, jumping as if over the scrolling line, or moving one hand down and the other away and up which, because of the fractured screen, causes the two hands to appear as if they are clapping.

However, through most of the video, Jonas's naked or scantily-clad inert body fills the screen. During these sequences, Jonas does not appear to have any agency which would allow her to interact with the scrolling. Instead, the bar appears to break apart her body, and the loud clapping only helps to assert the violent nature of these segments. For long moments the camera concentrates on the bare neck or midriff of Jonas providing the viewer an extended voyeuristic gaze. Because of the vertical roll, the viewer is tantalized as the camera begins to move above the waist or below the shoulders and then returns, endlessly repeating. The clapping and rolling are not only violent to the object of our gaze, however; the constant sound and movement is jarring, annoying, and even painful to the viewer's ears and eyes after twenty minutes of relentlessly repeating beats.

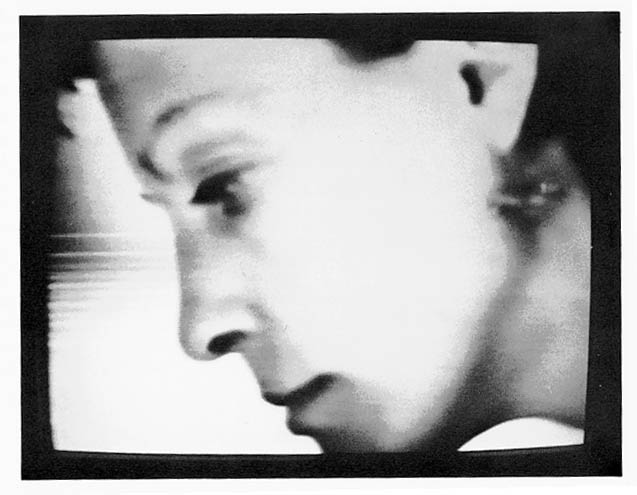

Finally, a change occurs. As the video comes to an end, Jonas's head appears between the viewer and the vertical roll. For the first time we see a whole figure. Her profile slowly comes into view, and then she turns her head to gaze out at the audience .

This final move is amazingly just as jarring as the vertical roll. Jonas looks at us with an accusing stare which disallows us from objectifyingly gazing any longer at her. Speaking of Vertical Roll, JoAnn Hanley remarks, "In this seminal work, Jonas constructs a theater of female identity by deconstructing representations of the female body and the technology of video." The woman performs as object of the male gaze, and her body is broken apart by the technological manipulation. The length and jarring quality of the video make it nearly impossible to not question the nature of the woman's sexualized performance. And, just in case you didn't get it, Jonas is sure to come in at the end and provide the knowing, accusing gaze that tells you you should be questioning your own gaze.

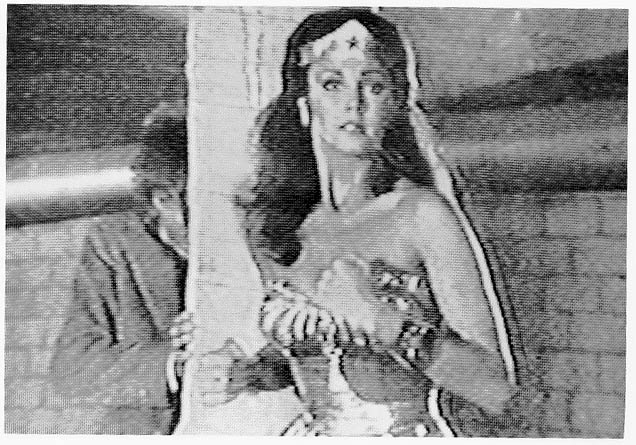

In 1978-79, Dara Birnbaum created a seven minute, color video entitled Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman. The first part of the video uses clips from the popular television series, Wonder Woman, and continually cuts, repeats, and reverses the images, concentrating on the moment of transformation of Linda Carter's character into Wonder Woman. The second part of the video includes a pop song of the late seventies disco era, "Wonder Woman in Discoland" by the Wonder Woman in Discoland Band; the song plays while the words scroll up a blue screen. A section of the lyrics to the song read as follows:

The ending disco song makes obvious society's need to sexualize powerful women as way of neutralization. The addition of the "oo"s, "uuu"s, and "ah"s to the written lyrics sways the listener to the final sexual (rather than violent) nature of the situation. It is no question that power--political, economic, physical--is generally accorded to men in our society. One must only think of the office place where, stereotypically, powerful men are admired and powerful women are referred to as "bitch" or "dyke". As early as 1929, Joan Riviere pointed out that women who attempted to gain power increased their performance of femininity so as not to be seen as intruding on the masculine position. Riviere writes, "Womanliness therefore could be assumed and worn as a mask, both to hide the possession of masculinity and to avert the reprisals expected if she was found to possess it".

This masquerade of womanliness or femininity is what Birnbaum turns inside-out in the rest of her video. Returning to the first half, we begin with a series of explosions and then see the transformation of woman in street clothes to woman in stars-and-stripes bikini .

This transformation which Birnbaum contends is the reason so many people sit through the rest of the bland television series provides every woman with the fantasy of power and every man with the fantasy of seeing Linda Carter practically disrobed in her spin cycle. After continually spinning into Wonder Woman, back into a conservatively-suited reporter, and back again, we see Wonder Woman cutting through her own image in a hall of mirrors and saving a weak man with only the deflective powers of her bracelets .

The video overflows with ironies. Wonder Woman ends up silencing herself and cutting her own throat by trying to escape the funhouse. We also learn that it is really only Wonder Woman's bracelets, the accoutrements of feminine sexuality, that are powerful; without them, Wonder Woman would be unable to stop bullets (whereas Super Man can simply catch speeding bullets in his bare hand). Like Wonder Woman of Discoland, the television super hero is really only super when sexualized and dressed accordingly. David Ross points this out nicely: "To reduce this to a simple formula, Birnbaum presents an action (transformation from powerless to empowered, helpless to savior) and suggests its consequence (intensified object of desire, no change in status, voice, or sensibility)."

As Riviere, and Judith Butler again in 1990, point out, the categories of femininity, power, and even woman can be donned or left behind by anyone--male or female. This performative aspect of gender is often missed or blindly accepted in the real world and on television. By exaggerating the artifice of the Linda Carter/Wonder Woman transformation, the artist makes obvious the performance. Birnbaum talks of her early video work including Technology: "Essentially, I attempted in my videowork from 1978-1982 to slow down the 'technological speed' of television and arrest moments of TV-time for the viewer, which would allow for examination and questioning." Birnbaum does more than leave the viewer open to objective questioning; by repeating and reversing the spinning transformation endlessly, the artist provides us with a dizzying, absurdly humorous look at the ridiculousness of gender performance.

Rosler, Jonas, and Birnbaum all use violence and repetition to make absurd and obvious the often taken for granted peformance of gender roles. Whether woman takes on the role of housewife/cook, sexualized object of the male gaze, or scantily clad savior, those roles are just that--roles in a play rather than natural ways of being. Video is the perfect medium in which to explore these performances because video allows an actual performance to be recorded and manipulated. Also, video is appropriate because many of the performances these artists are dealing with are only strengthened by commercial television's Mrs. Cleaver, Julia Child, porn star, or Wonder Woman.

But, all three of these works were created over twenty years ago. What has happened to the feminist video art since then? It still exists for sure. Women have not stopped making videos. However, there were definitely shifts in the art world, and society at large which caused a de-emphasis on the women working in alternative media. Toward the end of the seventies the feminist movement was greatly affected by emerging issues of race, class, and sexuality. The internal struggles were definitely necessary for the women's movement to progress and truly represent women of different backgrounds; but these protests from within the women's community upset the power which the feminist movement had been gaining.

In the 1980s, not only did the feminist art movement suffer from fracturing and shifting ideologies, but simultaneously, the male artists were regaining any ground they had lost in New York during the somewhat pluralistic seventies. At the turn of the decade, many male artists moved away from pop art, which was beginning to get swept up into the postmodern flow along with feminist art, and back toward a virile expressionist painting which easily found buyers. The boom in the art market in the early eighties paved the way for these collectible artworks to take precedence over less-collectible media, installation, and performance works--much more the territory of women artists. Whitney Chadwick writes of this period:

On MTV, music videos began to use some of the early ideas of repetition and manipulation to sink more meaningful messages into the seemingly mindless videos. In his study on Madonna, John Fiske points out that if you do not assume the young audience is a group of "cultural dopes", but instead has some agency and chooses to watch Madonna's videos, the meaning is greatly changed: "Her image becomes then, not a model meaning for young girls in patriarchy, but a site of semiotic struggle between the forces of patriarchal control and feminine resistance, of capitalism and the subordinate, or the adult and the young."

Madonna's "Boy Toy" image is being performed knowingly. She manipulates her audience into thinking that she is a helpless, sexualized woman, but retains the upper hand the entire time. In her video for "Material Girl" Madonna parades on stage (literally) in her finest while the tuxedoed men fall at her feet and bow to her every whim. However, in the video this is a performance and at the end, when the performance is over, she chooses to not accept the money and power her sexuality could get her but goes home with the blue-collar worker in his beat-up truck.

MTV has also provided a new arena in which "high" artists can reach a broader artist. For instance, electronic word artist, Jenny Holzer, has invaded the world of television; she has purchased commercial time on MTV in which she shows brief statements. Though her continual use of Truism-like language gets a bit tiresome, her silent messages cut through the noise of the Music channel splendidly. Some of her other commercial spots on other stations employ "talking heads" to read her messages. Using these people to disperse her commands adds a universality to her statements. Holzer discusses the possibilities brought out by her television spots: "I think having anything different on television will be inherently surprising or shocking to people. And then, if I used pointed content--it'll be amazing." Even an MTV-generation teenager can't help but look carefully and wonder what the message means.

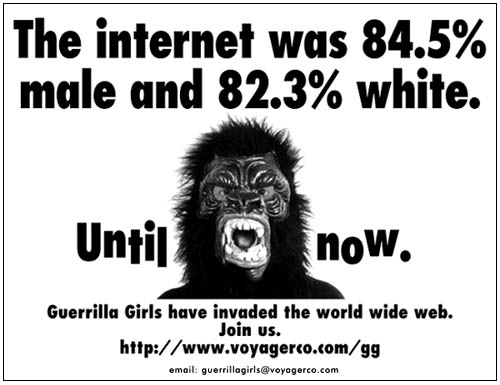

But when you start to question just how staged the Real World is and wish for the good ol' days of Thriller, even MTV becomes passŽ. Many women have moved out of television as eagerly as they moved into it, finding they could not be free enough in the corporate world. Instead, these women are taking advantage of the yet to be reigned in internet. For instance, the Guerrilla Girls (the self-proclaimed conscience of the art world famous for their satirical and statistical posters put up around SoHo) have chosen the world wide web as their new site of guerrilla artfare. Their website (http://www.voyagerco.com/gg/), like Holzer's television spots, unfortunately continues to use too much old material. The website is mainly a compendium of their tours and posters. However, their very presence on the internet is enough for the moment to keep their actions alive; an entirely new set of people is being reached over the modem lines, and as the Guerrilla Girls point out, this new audience is as much in need of diversification as is the art world.

Madonna knowingly plays with the meanings of labels such as material girl, boy toy, virgin, whore, and even madonna. Holzer uses the medium of television to display her Truisms such as "Raise boys and girls the same way", or "Abuse of power comes as no surprise". She speaks in the strong, authoritative voice and uses the medium usually associated with a masculine power thereby linguistically subverting the categories of masculinity and femininity and their relationship to power. The Guerrilla Girls blatantly attack the artworld and society at large for their sexism and racism. The Girls also play with gender roles by consciously referring to themselves as "girls" and by choosing to wear gorilla masks--a literal representation of gender as masquerade.

Exploring the female body as Wonder Woman or Material Girl is a practice that does not quickly grow old. Performance and video help to dismantle the perceptions of these categories and allow for the viewer to question what has been previously taken for granted. In the conclusion of his essay on feminist art, Henry Sayre makes a powerful juxtaposition between the eighties male painters and their contemporary feminist artists.

Madonna, Holzer, and the Guerrilla Girls are not necessarily using the same techniques of repetition and video manipulation. However, like Rosler, Jonas, and Birnbaum, they are continuing to explore, question, and subvert the assumed to be fixed categories of gender and power through various technological performances.

Bellour, Raymond. Eye for I: Video Self-portraits. New York: Independent Curators Inc., 1989.

Birnbaum, Dara. Rough Edits: Popular Image Video, Works 1977-1980. ed: Benjamin Buchloh. Nova Scotia, Canada: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1987.

Broude, Norma and Mary Garrard, editors. The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Crimp, Douglas, editor. Joan Jonas: Scripts and Descriptions 1968-1982. Berkeley, CA: University Art Museum, 1983.

Ferguson, Bruce. "Wordsmith: An Interview with Jenny Holzer", Jenny Holzer: Signs. Des Moines, IA: Des Moines Art Center, 1986.

Fiske, John. Reading the Popular. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989.

Guerrilla Girls. Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1995.

Hanley, JoAnn. The First Generation: Women and Video, 1970-75. New York: Independent Curators Inc., 1993.

Huyssen, Andreas. "Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism's Other", After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1986, 44-62.

London, Barbara. "Video: A Selected Chronology, 1963-1983", Art Journal, Fall 1985, 249-262.

Olander, William. Women and the Media: New Video. Oberlin, OH: Oberlin College, Allen Memorial Art Museum, 1984.

Owens, Craig. "The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism", The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Edited by Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay Press, 1983, 57-77.

Pollock, Griselda. "Painting, Feminism, History", Destabilizing Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates. Edited by Michele Barret and Anne Phillips. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

Rasenberger, Jean. "In the Beginning: The First Generation: Women and Video, 1970-75 at the Long Beach Museum of Art", Artweek, July 21, 1994, 16-17.

Riviere, Joan. "Womanliness as a Masquerade", Formations of Fantasy. Edited by Victor Burgin, et al. London: Methuen, 1986, 35-44.

Ross, David. "Truth or Consequences: American Television and Video Art", Video Culture: A Critical Investigation. Edited by John Hanhardt. Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986.

Sayre, Henry. "A New Person(a): Feminism and the Art of the Seventies", The Object of Performance: The American Avant-Garde Since 1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, 66-100.

Sturkin, Marita. "Feminist Video: Reiterating the Difference", Afterimage, April 1985, 9-11.

Walker, John A. Art in the Age of Mass Media. London: Pluto Press, 1994.

Wooster, Ann-Sargent. "Why Don't They Tell Stories Like They Used To?"" Art Journal, Fall 1985, 204-212.