Professor Vesna

December 12, 1997

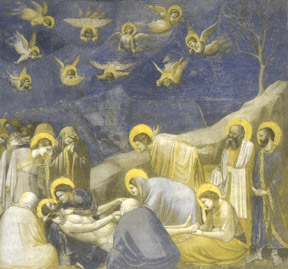

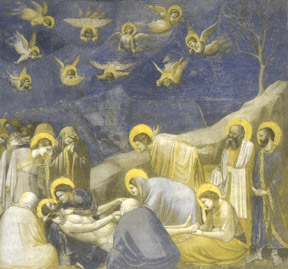

The revolution unleashed by Giotto would experience phenomenal development, transformation, and ultimately interrogation over the following seven centuries. From the early experiments of Giotto, to the towering skyscape of Annibale Carracci's Farnese Gallery (fig. 2)3, to the startlingly precise cityscape of Richard Estes's 34th Street, Manhattan, Looking East, 1979 (fig.3)4, artists found a near-infinite number of ways to fool the viewer into believing a lie, as paint on a two-dimensional surface pretended to be trees, people, cars, clouds, and buildings.

Simultaneous with this deconstruction of illusionism in painting, a new form of illusionism has emerged from the realm of science fiction into technological reality. Advances in computer interface technology have reintroduced the possibility of fooling the viewer into believing a lie; while we are wise to the tricks of painters and sculptors, the trompe l'oeil techniques of digital technology may prove far more insidious. Computer graphics have infiltrated, and in some cases completely overtaken, movies and other forms of entertainment. And, Virtual Reality has just begun to realize potential applications in fields from medicine to art to engineering. We are now able to create remarkably convincing moving images of things which never existed, we are able to manipulate existing documents to record an entirely new set of events, and we are able to engage not only sight but all the senses in an immersive environment constructed entirely out of computer memory. With these emergent technologies have come equal doses of optimism and apprehension. Advocates claim that these advances will lead to an improvement in the quality of life while skeptics warn against losing control of these powerful tools.

It should be remembered, however, that computers are neither good nor evil; they are tools at the disposal of artists, engineers, doctors, businessmen, and politicians. Like paintbrushes, scalpels, or automobiles, they are, as described by Marshall McLuhan, merely extensions of ourselves.7 Nevertheless, just as we manipulate a keyboard or a data glove, computers will manipulate the society of the next century as we integrate new technology into our experience and understanding of the world. My goal is to explore the paths that these developments are currently taking and may take in the near future. And, what the consequences may be for society, and in particular, for artists and their audiences. The computer revolution has already had a radical effect on many segments of society, and it is reasonable to expect that it may soon unleash changes in art as profound as those of Giotto, seven-hundred years ago.

In June of 1993 Steven Spielberg released Jurassic Park, ushering in a new era of special effects in film (fig. 4)8. Computer graphics were introduced to film as early as 1973's Westworld,9 and computer generated characters date back to 1985's Young Sherlock Holmes.10 However, Jurassic Park represents the first movie in which, as Ross Harley describes: "The seamless superimposition of the computer models matches the live action perfectly....the fantasy is so compelling that we can imagine live dinosaurs in our world."11 Spielberg's film went on to gross $236 million dollars in its first thirty days of release as audiences gazed in awe at the massive brontosauruses and recoiled in terror at the relentless velociraptors. Just as the scientists in the movie had resurrected long-extinct species from DNA fragments trapped in amber, Spielberg's special-effects wizards did the same with computers, programming in minute details of skin texture, anatomical structure, and even the dynamics of a stampeding herd.

While the manipulation of human images and their placement in altered contexts may offend our sensibilities, it is far from new. In fact, it is artists who first introduced the technique of appropriation. From the cubist collages of Picasso and Braque to Warhol's Campbell's soup cans to work by contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons, artists have recontextualized and altered existing imagery for a variety of purposes. And, as a result of these often aggressive experiments the contemporary audience has become acutely aware of questions of originality and authorship in art and entertainment. While copyright laws and artists' contracts will likely catch up with technological advances in the coming years, the cultural landscape has been irrevocably changed. It will be years, if ever, before actors and other artists may be replaced by computer memory files which create a convincing simulation, but a precedent has been set in which an illusion can be every bit as convincing as reality. As the illusionistic capacities of computer graphics renders the process of appropriation indistinguishable from the act of creation, the death of the author described by Roland Barthes becomes complete.19 The contemporary artist finds him/herself on the cusp of a world in which a copy is every bit as viable as the original and the imitator is just as creative as the innovator.

In all of the previously mentioned examples, the digital effects were created over a span of months, demanding massive amounts of both human and computer labor. However, within the next decade, faster computers and more sophisticated software will improve the efficiency of computer graphics technology to the point that it will be possible to alter video footage almost instantaneously.20 The comfortable cushion of time which allows the viewer to recognize Clinton's speeches in Contact as fictional will be erased, as everything from sporting events to the evening news will be subject to convincing digital manipulation. I am not suggesting that television networks will manufacture spectacular car crashes or alter the president's words for the sake of boosting ratings. As long as competition exists between sources, discrepancies of fact will allow audiences to quickly perceive any gross manipulation.21

Very serious problems arise, however, when documentary evidence must pass through a channel of limited access. The Gulf War of 1991 provides an illustration of this condition, in which virtually all images of the war passed through military hands. Critics of the government assert, as evidenced by the words of Avital Ronell, that the military carefully omitted any footage which revealed either United States or Iraqi casualties, creating the image of a bloodless and noble war: "Orificial shutdown and excremental control help explain why the Gulf War was conducted under the compulsive sign of cleanliness....It was so clean, in fact, that there were blank screens assuring the protocols of propriety -- the covering up of coverage...."22 The lasting image of the war, for most United States citizens is of nighttime bombing raids which resemble the video game Space Invaders more than the bloody and chaotic newsreels of previous wars. Looking towards the future, computer graphics technology creates the possibility of not only censoring, but actively altering, or even manufacturing, documentary evidence.

While the prospect of digitized propaganda may smack of paranoia, it does point towards a future in which the public will be far less willing to accept an image as an accurate representation of the truth. Contemporary society accepts that a reporter may sometimes infuse a story with his/her own opinions or biases, selecting images or quotations which paint a subjective view of a story.23 Thus documentary media such as photography and film have become understood not as incontrovertible reality, but as one particular perspective on reality. Nevertheless, we still accept almost without question that the images which beam into our television sets or arrive in the morning paper do represent a particular perspective upon a tangible reality; in order for a photograph or film to be created by traditional means necessarily demands a corporeal subject. As computers create increasingly convincing illusions of reality created entirely from ones and zeroes, the very notion of documentation of reality may fall under increasingly acute suspicion. The previously mutually exclusive terms of journalism, editorializing, and entertainment are revealed as tightly interrelated aspects of a common action: the communication of information from one source to another.

This interrogation of the information which orders contemporary life reveals not just a fascination with, but a dependence on media. Before the advent of the telephone, television, and computer, the average person existed in a much smaller metaphysical sphere than his/her counterpart today, limited by the constraints of physical travel. Long-distance communication was limited to printed media -- published books and hand-written correspondence -- and these had to be physically transported across land or sea. As a result, reality existed effectively only as far as one could see or hear; anything beyond the senses of the individual had to be abstracted into language. In marked contrast, at the close of the twentieth century, the push of a button on the television or personal computer can produce images, sounds, and information originating from virtually any corner of the world. William J. Mitchell describes this transformation:

As the fin-de-K countdown cranked into the nineties, I became increasingly curious about the technicians I saw poking about in manholes. They were not sewer or gas workers; evidently they were up to something quite different. So I began to ask them what they were doing. "Pulling glass," was the usual reply. They were stringing together some local, fiber-optic fragments of what was fast becoming a worldwide, broadband, digital telecommunications network. Just as Baron Haussmann had imposed a bold spider's web of broad, straight boulevards on the ancient tangle of Paris...these post-whatever construction crews were putting in place an infobahn -- and thus reconfiguring space and time relationships in ways that promised to change our lives forever.24

The modern lifestyle has become inseparable from this infobahn and the media which accompany it. We communicate with far-away family, friends, and colleagues, we conduct business across the country and around the world, and we learn of world events which affect us, from tomorrow's weather to international politics. Through the light speed network of telephony, television, and now the internet, we have extended ourselves drastically beyond our physical limitations.25 And, as we have learned to trust these digital prosthetics as we trust our own eyes, ears, or hands, our experiential reality has expanded to reach virtually to infinity.26

Of course, the information transmitted by technological inventions is no more trustworthy than that of the physical senses. The five human senses are subject to inherent limitations, imperfections, damage, and even elaborate hallucinations. The sights, sounds, and other sensations which the mind perceives may, for a variety of both physical and psychological reasons, have little relation to the data which the sense organ initially receives. In the words of Howard Rheingold:Ê"We habitually think of the world as 'out there' but what we are really seeing is a mental model, a perceptual simulation that exists only in our minds."27

As technology infiltrates the modern experience at an increasing rate, reality becomes an entirely relativistic term, constantly recreated and redefined by all the extensions of man and all the forms they may take. Trusting media such as television, film, and the internet certainly creates inherent dangers, as they are, to a greater or lesser extent, the common property of all who possess access to them. While our eyes, ears, and hands are linked directly to our mind through our nervous system, these new technological senses must pass through many hands with many different agendas before they reach the viewer. Advances in computer graphics represent a new level of control over these technologies, and thus the possibility for greater control over their audiences.

However, just as the capacity for manipulation and fabrication is increased, so is the sensitivity to these illusions on the part of the audience. To illustrate this point, I would like to call to mind George Lucas's Star Wars trilogy. The original Star Wars, released in 1977, was a special effects marvel, utilizing stop-action photography and miniaturized models (including several sticks of chewing gum and a pair of tennis shoes posing as distant space ships)28 to create what were, at the time, incredibly convincing illusions. However, by the 1983 release of the third movie in the series, Return of the Jedi, the original Star Wars appeared decidedly dated. Eight years of movie-going had conditioned audiences to interpret the visual codes of flying spaceships and fierce monsters more efficiently and accurately, until the illusionistic devices which propelled Star Wars were no longer sufficient. Similarly, as computerized graphics continue to improve, the audience will learn to recognize the inconsistencies between reality and illusion, no matter how small they become. In lower-resolution media such as television, in which these gaps may be erased completely by the inherent limitations of the medium, audiences will become more sensitive to the pedigree of the media they receive, and evaluate the value and reliability of the information accordingly.29

One of the buzzwords of the nineties, virtual reality presents a brand of illusionism distinctly different from that of movie or television special effects.30 In a movie such as Jurassic Park or Toy Story, the viewer is aware of the space between technology and human perception. However precisely modeled they may be, the dinosaurs are not presented as live dinosaurs stampeding across the front of the theater, but as two-dimensional images of dinosaurs projected on a screen. Thus the illusion is not perceptual, but cognitive in nature; the audience accepts the reality of the dinosaurs because they accept that film represents a reality which exists in some other place or time. In contrast, the goal of immersive virtual environments is to render the means of interface completely invisible, thereby creating illusion at the level of sensual perception. Robbed of this gap between media and sense, the mind is theoretically unable to distinguish between reality and illusion.

In order to understand virtual reality technology, it is vital to first separate scientific truth from media myth and to detangle the duplicitous and loaded vocabulary which has developed around it. N. Katherine Hayles provides a working definition of "virtuality" as "the perception that material structures are interpenetrated with informational patterns."31 As this paper attempts to illustrate, "reality" is a term far too imprecise to be applied on only one side of the border between humans and technology; Mary Anne Moser suggests the term "virtual environment" as far less problematic and sensational than "virtual reality."32 It must also be established that virtual environments are an interactive media. The environment is rarely tied to a single linear narrative structure, instead responding to the actions and reactions of the participant. The creation of an experience becomes a collaborative effort between programmer, computer, and participant. A virtual environment can therefore be defined as an environment in which all the senses are engaged by an integrated and interactive network of hardware, software, and humanity.

The term "virtual reality" dates back at least to 1965, when Ivan Sutherland proposed his "ultimate display:"

The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.33

It is this hallucinatory video game conception of virtual reality which has dominated the public imagination to the present day. As a result, the present applications reflect such a vision, dominated by (1) the military, and (2) the entertainment industry. Flight simulators, combining actual airplane cockpits with video monitors in place of windows have become so convincing that a pilot in training once fainted when he made an error in judgment which caused his virtual 747 to end up in a ditch.34 And, the head-mounted display (a helmet equipped with close-range stereo video monitors and headphones) and data glove (a glove which allows movements of the hand to control a computer) are already being marketed to the public as accessories to video game systems.

The potential of virtual environments, however, has only begun to be tapped, as both hardware and software are poised to make drastic leaps in the coming years. Cumbersome helmets may be replaced by featherweight wraparound sunglasses and the date glove may give way to a for more responsive data suit. An even more radical solution is described by Dr. Thomas A. Furness III: "At the HIT Lab, we are working on the 'Virtual Retinal Scanner,' a device that uses lasers to create an image in the eye....The retina itself becomes the screen....There is not a physical picture as there is in a television set or liquid crystal device. The picture does not exist 'outside' anywhere."35 In this environment, the interface is not a glorified keyboard or a high-definition monitor, but the eye itself, thus collapsing the distance between physical and informational altogether. For the ultimate embodiment of the virtual environment, it is still necessary to turn to science fiction; each of the ships in the current Star Trek series are equipped with a "holodeck," a room which is able to generate holograms which are convincing to the eyes and ears, as well as tangible to the touch. Characters are able to converse with a virtual Leonardo da Vinci, battle digitized Klingon warriors, or bask in the sun on a beach that is actually light years away.36

More immediate than science fiction fantasy, doctors imagine medical applications in which they are able to practice difficult operations on virtual patients, even consult with other surgeons who may be half-a-world away. Architects imagine applications in which the client can walk through a virtual model of his/her project proposal. Educators imagine classrooms in which students from rural Iowa and inner city Los Angeles can learn from the same teacher in suburban Paris. In short, virtual environment technology offers the possibility to go anywhere, do anything, be anyone, in a world liberated of physical limitations or perils.

All of these possible manifestations point to a desire to eliminate the physical body from the human experience.37 Frustrated with the imperfections and limitations of carbon-based life, the mind, it seems, has undertaken the project of creating an alternate universe in which computers become the vessels for human consciousness. Hayles, in her discussion of artist Catherine Richards, explains:

...We in first-world countries are already convinced of our own virtuality. Everything else is becoming virtual -- money is displaced by automatic teller machine (ATM) cards, physical contact by phone sex, face-to-face communication by answering machines, an industrial economic base by information systems; why shouldn't our bodies be virtual too?"38

The consequences of such a fundamental shift in the conception of what it means to be "human," even in the present fledgling state, are both numerous and serious. First and foremost, it is necessary to understand that immersion in a virtual environment represents a power relation between human and computer. Michel Foucault, in his examination of power relations between the body and social institutions, identifies "subjectification" as the "way a human being turns him- or herself into a subject,"39 willingly accepting the domination of a surrounding structure, be it physical, political, or personal. The virtual environment represents a form of subjectification in which the participant places him/herself under the control of an illusion, immersing him/herself in a sea of digital information designed to imitate the physical world. Certainly Foucault would recognize the irony of "liberating" human consciousness by encasing the body in a suit of circuitry or etching vision on the retina with lasers. Regardless of whether or not virtual environments free the mind from physical limitations, it represents an unprecedented imprisonment of the body.

In "On Visions, Monsters, and Artificial Life," Brenda Laurel draws a parallel between modern advances in virtual reality and the emergence of drama in Classical Greece: "Plato banned the art of drama from his Republic because he thought humans were in danger of confusing art and life."40 Just as Plato feared that the dramatic character could become indistinguishable from the identities of the audience, those suspicious of virtual reality have proposed, particularly as technology creates more convincing environments, that the participant may become unable to distinguish between digital illusion and the world outside of that illusion.41 While this represents a long-established distrust on the part of humans towards their own inventions (and, by extension, a deeper mistrust of themselves), immersion within a virtual environment radically transforms individual identity into a far more multiplicitous and malleable construction. Once separated from the body, the subject is able to attach itself to an almost infinite variety of personas. This is already clearly in evidence in the more abstract virtual reality of cyberspace, in which those online are able to form an online identity which may be very different from their "everyday" identity.42 Free to interact with others online without the specifying consequences of physical interaction, the permutations of personality become infinite: male is free to become female, weak can become strong, conservative can become liberal. As virtual environments allow participants to paint these surrogate identities in increased clarity, as text gives way to sight and sight, the virtual identity may become as "real" as the physical identity. Thus the postmodern identity, a fractured collection of constructed subjective realities, becomes the foundation of the human condition.

Ultimately, it becomes clear to the subject that the world of virtual reality -- the environment created out of binary information by a computer -- is as "real" as the physical world. The window created by technology leads to a reality every bit as interactive and convincing as the world outside our bedroom window, where the participant can make or lose money, make friends and enemies, and even fall in and out of love. The term "virtual" implies a depthless copy of "reality." In fact, the visual, aural, and other illusions which define the virtual environment serve as a point of entry into what can only be described as an independent informational reality. We are thus witnessing the birth of a new epistemology which radically erodes the model of the world which has dominated human thought and action since the Enlightenment. As long as the body is sufficiently contained within the technological apparatus, and therefore insulated from the virtual identity, the participant in a virtual environment is able to live a life which is temporarily suspended from the biological and physical laws which have long been taken for granted. This should not be viewed as a paradise, an electronic Eden free of organization and structure. Quite the contrary, the virtual reality can be expected to develop structures of power according to the parameters of this new reality. While we presently compete for the biggest guns, the fastest cars, the most attractive sexual partner, we may soon compete for the most powerful computers, the fastest fiber-optic transportation, or the best virtual real estate.

To this point, the role of artists in relation to emerging computer technologies has been treated only in passing. This is neither by oversight or coincidence; computer graphics and virtual environments have thus far been the almost exclusive province of scientists. While the business and political worlds are beginning to embrace this technology, the art world has been extremely hesitant to engage and utilize digital technology.43 This is undoubtedly a combination of the prohibitive cost, technical difficulties, and inherent personal biases. Nevertheless, in light of the long fascination with illusionism on the part of the artist, it seems ironic that he/she has not embraced what is perhaps the ultimate in illusionistic media with more zeal. Quite the contrary, the vast majority of artists who have begun to explore digital technology have opted to, in the words of Will Bauer and Steve Gibson about their work Objects of Ritual, "argue for/against the use of virtual reality as a tool for distortion rather than mimesis. [Objects of Ritual] questions the commonly held assumption that virtual reality is primarily useful as an imitator of the real and a simulator of certain realities. Virtual reality distorts, manipulates, and it tells lies -- like all art."44 Bauer and Gibson firmly establish the artist as a destroyer, not a maker, of illusion, discovering and probing the interstices between physical reality and virtual reality.

Giorgio Vasari defined the highest goal of the artist and the central project of the Renaissance, first embodied in the art of Giotto, as the faithful attention to nature.45 As the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque and later styles, artists utilized illusionistic techniques to transcend the boundaries of nature. Ironically, as the capacity for the creation of illusion has become all but absolute through modern technology, the artist finds him/herself back at the beginning. The worlds created by digital technology are ripe for a critical exploration on the part of the artist. Even an introductory examination of computer graphics and virtual environments reveals complex questions of perception, identity, and power relations. While science has created these technologies, and industry has found was to utilize them, it will be the task of the artist to untangle the increasingly complex web of reality and illusion which they have created. This will occur through a critical observation of the possibilities and limitations, as well as the content and context of these emerging digital worlds. The three-dimensional physical world is rapidly giving way to the many-dimensional world of information and illusion. Much like the painter relates two dimensions to three, the artist will soon be called upon to relate three to four, four to five, and so on. While "reality" at the dawn of the twenty-first century has become a baffling collection of subjectivities and hallucinations, the task of the artist is, just as it was in the time of Giotto, through the careful observation of reality, in whatever form it may take, to create a window into space.

Selected Bibliography

Aukstakalnis, Steve and David Blatner. Silicon Mirage: the Art and Science of Virtual Reality. Stephen Roth, ed. Berkeley, CA: The Peachpit Press, 1992.

Auzenne, Valliere Richard. The Visualization Quest: a History of Computer Animation. London: Associated University Press, 1994.

Battock, Gregory, ed.Super Realism: A Critical Anthology. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975.

Burke, Sean. The Death and Return of the Author: Criticism and Subjectivity in Barthes, Foucault, and Derrida. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1992.

Coatney, Mark. "Forrest Clinton: Clinton lawyers upset about the president's role in 'Contact.'" Time Magazine, July 14, 1997.

Creighton, Gilbert E. "Giotto." The Dictionary of Art. Jane Turner, ed. New York: Groves Dictionaries, Inc., 1996.

Duran, Lorene M. "'Humanipulation': Legal Considerations in the Computer Animated Manipulation of the Human Image in Feature Film." http://www.regent.edu/acad/schcom/ rojc/duran/human.html.

Finch, Cristopher. Special Effects: Creating Movie Magic. New York: Abbeville Press, 1984.

Foucault, Michel. "The Subject and Power." Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Greenberg, Clement. Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston, 1961.

Harley, Ross. "An Archaeology of Spielberg's Jurassic Park." http://www.uiah.fi/ bookshop/isea_proc/high&low/03.html.

Janson, H. W. History of Art. 4th ed. Anthony F. Janson, ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991.

Jay, Martin. Downcast Eyes: the Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Krenis, Karen. "Adventures in Toyland: Disney's all-computer 'Toy Story' marks a first for animated films" The Detroit News. November 4, 1995.

Laurel, Brenda, ed. The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesly Publishing Co., Inc., 1990.

Leebaert, Derek, ed. Technology 2001: the Future of Computing and Communications. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991.

Mastai, M. L. d'Otrange. Illusion in Art: A History of Pictorial Illusionism. New York: Abaris Books, 1975.

McCullough, Malcolm. Abstracting Craft: the Practiced Digital Hand. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Meisel, Louis K. Photorealism Since 1980. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987.

Mitchell, William J. City of Bits: Space, PLace, and the Infobahn. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995.

Moser, Mary Anne and Douglas MacLeod, eds. Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments. For the Banff Center for the Arts. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996.

"New Developments in Computer Technology: Virtual Reality." Hearing Before the Subcommitte on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate. 102nd Congress, 1st session, May 8, 1991.

"Revolution in a Box, part 2: When Seeing is No Longer Believing." ABC News: Nightline. September 9, 1997.

Smith, Michael R. "Postmodernism Influences on Modern American Journalism News Conventions" http://www.regent.edu/acad/schcom/rojc/ smith/postmod.html.

Smith, Thomas J. Industrial Light & Magic: the Art of Special Effects. New York: Ballantine Books, 1986.

Sutherland, Ivan. "The Ultimate Display." Information Processing, 1965: Proceedings if IFIP Congress 65. Washington, D.C.: Spartan Books, 1965.

Vasari, Giorgio. The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Vol. 1. William Gaunt, ed. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1970.

. 1H.W. Janson, History of Art, 4th ed., Anthony F. Janson, ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991) 398.

2Gilbert E. Creighton, "Giotto," The Dictionary of Art, Jane Turner, ed. (New York: Groves Dictionaries, Inc., 1996) 681.

3Janson 552.

4John Arthur, Richard Estes: Paintings and Prints (San Francisco: Pomegranite Art Books, 1993) 40.

5Clement Greenberg, Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston, 1961).

6Gerrit Henry, "The Real Thing," Super Realism: A Critical Anthology, Gregory Battock, ed. (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975) 3.

7Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

8Image courtesy of http://www2.msstate.edu/%7Ebrb1/pics/slide07.jpg.

9Valliere Richard Auzenne, The Visualization Quest: a History of Computer Animation (London: Associated University Press, 1994.) 21.

10Thomas J. Smith, Industrial Light & Magic: the Art of Special Effects (New York: Ballantine Books, 1986) 211-214.

11Ross Harley, "An Archaeology of Spielberg's Jurassic Park" (http://www.uiah.fi/ bookshop/isea_proc/high&low/03.html).

12Image courtesy of http://www.disney.com/DisneyBooks/new/toy/ToyStory/Today/ ToyStory7.html.

13Karen Krenis, "Adventures in Toyland: Disney's all-computer 'Toy Story' marks a first for animated films," The Detroit News, November 4, 1995 (http://detnews.com/menu/stories/

23529.htm.

14Image courtesy of http://www.ozcraft.com/cgi-ozcraft/picview.pl?gump/gump_ kennedy.jpg

15Mark Coatney, "Forrest Clinton: Clinton lawyers upset about the president's role in 'Contact,'" Time Magazine, July 14, 1997.

16Lorene M. Duran, "'Humanipulation': Legal Considerations in the Computer Animated Manipulation of the Human Image in Feature Film" (http://www.regent.edu/acad/schcom/ rojc/duran/human.html).

17ibid.

18ibid.

19Sean Burke, The Death and Return of the Author: Criticism and Subjectivity in Barthes, Foucault, and Derrida (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1992).

20James Cameron, "Revolution in a Box, part 2: When Seeing is No Longer Believing," ABC News: Nightline, September 9, 1997.

21A clear example of this occured on December 1, 1997 when both Time and Newsweek ran cover stories on the septuplets born to Bobbi and Kenny McCaughey. Readers quickly noticed that one of the magazines had airbrushed the mother's teeth to make her more photogenic while the other had left her image unaltered.

22Avital Ronell, "A Disappearance of Community," Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod, eds. for the Banff Center for the Arts (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996) 121-122.

23Michael R. Smith, "Postmodernism Influences on Modern American Journalism News Conventions" (http://www.regent.edu/acad/schcom/rojc/smith/postmod.html).

24William J. Mitchell, City of Bits: Space, PLace, and the Infobahn (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995)3.

25McLuhan ????

26The Hubble Space Telescope has provided images of space nearly to the spatial and temporal boundaries of the universe.

27Howard Rheingold, "What's the Big Deal About Cyberspace," The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, Brenda Laurel, ed. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesly Publishing Co., Inc., 1990) 449.

28Cristopher Finch, Special Effects: Creating Movie Magic (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984) 11.

29"Revolution in a Box, part 2: When Seeing is No Longer Believing."

30I have chosen not to include figures of any virtual environments because the 2-dimensional film still cannot begin to communicate a medium which depends on all the senses, as well as the capacity for interactivity and the passage of time.

31N. Katherine Hayles, "Embodied Virtuality : Or How to Put Bodies Back Into the Picture," Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod, eds. for the Banff Center for the Arts (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996) 4.

32Mary Anne Moser, "Introduction," Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod, eds. for the Banff Center for the Arts (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996) xviii.

33Ivan Sutherland, "The Ultimate Display," Information Processing, 1965: Proceedings if IFIP Congress 65 (Washington, D.C.: Spartan Books, 1965) 508.

34Dr. Fred Brooks, "New Developments in Computer Technology: Virtual Reality," Hearing Before the Subcommitte on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate, 102nd Congress, 1st session, May 8, 1991, 11.

35Dr. Thomas A. Furness III, "New Developments in Computer Technology: Virtual Reality," Hearing Before the Subcommitte on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate, 102nd Congress, 1st session, May 8, 1991, 32-35. Dr. Furness predicts the completion of a working prototype within "3 to 5 years" (from 1991).

36Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space, and Star Trek Voyager, various episodes.

37Hayles 1-3.

38Hayles 23.

39Michel Foucault, "The Subject and Power," in Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982) 208.

40Brenda Laurel, "On Visions, Monsters, and Artificial Life," The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, Brenda Laurel, ed. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1990) 481.

41Hayles 23.

42Mitchell 27.

43Moser xxiii-xxiv.

44Will Bauer and Steve Gibson, "Objects of Ritual," Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod, eds. for the Banff Center for the Arts (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996) 274.

45Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, vol. 1, William Gaunt, ed. (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1970) 65.