Whether smoked in a peace pipe by

the Indians or in cigarettes by Hollywood stars, tobacco is intertwined with

the history of this continent. Even now, in the midst of the anti-smoking campaign,

it is no less a preoccupation: nowhere in the world are people so adamantly

and passionately against smoking. From a pure ritual of the Indians, smoking

was transformed into a commercial, addictive, cancerous industry. Hopefully

one day we will again discover the ritual...

Several

years ago I had to pass through a cigar factory regularly on the way to my workspace.

Seeing the women making cigars made me curious about tobacco, smoke and fire.

I am not a smoker and yet, as if drawn by a magnet, I went further and further

into the symbolism of the cigar and tobacco leaf. With this unlikely subject

to consume me, I got in touch with a memory deep inside each one of us: when

the first spark produced the first flame. I went far from my background in Yugoslavia,

to a culture entirely different, in Africa, only to discover this same memory.

Several

years ago I had to pass through a cigar factory regularly on the way to my workspace.

Seeing the women making cigars made me curious about tobacco, smoke and fire.

I am not a smoker and yet, as if drawn by a magnet, I went further and further

into the symbolism of the cigar and tobacco leaf. With this unlikely subject

to consume me, I got in touch with a memory deep inside each one of us: when

the first spark produced the first flame. I went far from my background in Yugoslavia,

to a culture entirely different, in Africa, only to discover this same memory.

The spirit of lightning and fire

is everywhere, and as this natural force traveled, it was colored by the different

cultures it touched, given a variety of names and forms by the minds it inspired,

the hearts it penetrated: the energy with which the World began, with which

it will end, the energy of Fire, the Creator and the Destroyer.

The

first memory I have of tobacco is from my childhood in Indonesia. I remember

rice fields, tea fields and tobacco fields. I remember men and women not only

smoking hand-rolled cigarettes, but chewing tobacco. Their teeth would rot from

it, and when they smiled, a bright Red stain flashed. Another strong memory

from this period surfaced many times as I delved into the tobacco smoking story

The

first memory I have of tobacco is from my childhood in Indonesia. I remember

rice fields, tea fields and tobacco fields. I remember men and women not only

smoking hand-rolled cigarettes, but chewing tobacco. Their teeth would rot from

it, and when they smiled, a bright Red stain flashed. Another strong memory

from this period surfaced many times as I delved into the tobacco smoking story

My parents took us to a funeral rite

in Bali. It was twilight. There were many dressed-up people, dancing and feasting;

it was a great celebration. When the funeral procession finally emerged, everyone

was so excited. A group of men came out carrying the corpse, which was wrapped

in a huge banana leaf and covered with lotus flowers. The structure upon which

the corpse was placed was built from bamboo sticks, and to me it seemed endless

in height. When they brought out his wife, the crowd went into a frenzy. She

was dressed in the finest embroidered silks, covered head to toe in jewels and

wore a gold crown on her head, with flowers all over. She climbed onto a tall

ladder and sat next to her late husband. At this point my memory blurs. They

proceeded to light the structure on fire. It became my nightmare. Someone said

that the bride goes to the heavenly abode with the husband. My father assured

me that this is not the case anymore; there is a law against it. I don't know

to this day what happened.

I had nightmares for years after.

Did she scream in the flame? Did she die with the man wrapped in the banana

leaf? Twenty years later, while traveling through India, I saw a TV show about

Sati, the practice of putting to death the bride of the dead man. Apparently,

to this day it goes on. In fact the subject of the show was a sixteen-year-old

bride who was put to death that year in a village. In Sati, a woman is drugged,

then a group of men come to the home and start dancing around her, chanting

a death song, and then they kill her. This is a way to ensure that the inheritance

stays in the husband's family and is not passed over to the wife. If somehow

the woman manages to escape this dreadful fate, she is doomed in the community

and may end up killing herself in despair or turning to prostitution to survive.

One of the images from this show that stuck in my mind was a rally of villagers

protesting the law which forbade the custom of bride burning. Behind the main

speaker was a picture of a beautiful woman enveloped in flames. The audience

was composed of angry chanting men. It sends a shiver through my spine.

Raised in an atheistic environment,

I've never been taught a religion. This made me free to enter temples, churches,

mosques and synagogues and marvel at the spiritual source in much the same way.

The theatrical quality of religious rituals moves me. I especially feel close

to the ancient nature religions, particularly Zoroastrianism, because there

the element of fire is central to worship. In Zoroastrianism, fire is believed

to be the son of God and is called on as a Warrior. The most sacred of fires,

the Bahram fire, is required in order to do battle with the spiritual demons

of darkness.

Millennia

of millennia ago, my ancestors migrated from the Himalayas. This warrior tribe

walked for miles, making rest stops of a few days, then continuing on to look

for their new home. They needed a sign in order to settle down. The sacred fire

was carried in golden pots and was never allowed to die out. Not only was it

a source of spiritual strength, warmth and light, it was also a protection against

wild beasts at night. When they reached the river Danube, they were very impressed

and decided to rest awhile on this fertile soil. That very night a bolt of lightning

struck at the center of the river and a two-headed bird came out with a loud

thunderclap. At its stomach was a Red and blue spiral which revolved with great

speed and emanated tremendous heat. Then the bird turned into a puff of smoke

and disappeared. Since the tribe worshiped Perun, the God of Thunder, they knew

that this was the auspicious sign they were looking for, and made this land

their home. Somewhere in my genetic makeup, the memory of this story is encoded.

Millennia

of millennia ago, my ancestors migrated from the Himalayas. This warrior tribe

walked for miles, making rest stops of a few days, then continuing on to look

for their new home. They needed a sign in order to settle down. The sacred fire

was carried in golden pots and was never allowed to die out. Not only was it

a source of spiritual strength, warmth and light, it was also a protection against

wild beasts at night. When they reached the river Danube, they were very impressed

and decided to rest awhile on this fertile soil. That very night a bolt of lightning

struck at the center of the river and a two-headed bird came out with a loud

thunderclap. At its stomach was a Red and blue spiral which revolved with great

speed and emanated tremendous heat. Then the bird turned into a puff of smoke

and disappeared. Since the tribe worshiped Perun, the God of Thunder, they knew

that this was the auspicious sign they were looking for, and made this land

their home. Somewhere in my genetic makeup, the memory of this story is encoded.

As a child

I spent many hours playing in the swimming pool, going up and down the metal

slide. Once while I was playing alone in the pool, it started raining, but in

Indonesia, tropical rains are usually ignored. They vanish as suddenly as they

appear. Flashes of lightning were sparking through the twilight sky. I lay on

my back in the water, floating, and was looking up in astonishment. This peaceful

moment was cut short by my father, who ran out shouting sternly that I must

immediately get out. I was puzzled by his behavior, and he screamed furiously

that I could have been electrocuted! This was a shocking idea to me. Images

of the lightning hitting my body kept going through my head. I kept trying to

imagine how it would feel, lightning hitting me.

It

was a hot, quiet summer, 1985. Our family had gathered at the familiar spot,

the house in Motovon, Yugoslavia. Motovun is a magical 13th century Venetian

town on top of a hill twenty minutes away from the sea, which makes for a great

distance from the hustle and bustle of the tourist-crazed coast. The river Mirna,

which used to bring ships from the sea to this merchant town, has all but evaporated,

and Daytona, as it was called by the Italians, is blissfully removed from the

world.

It

was a hot, quiet summer, 1985. Our family had gathered at the familiar spot,

the house in Motovon, Yugoslavia. Motovun is a magical 13th century Venetian

town on top of a hill twenty minutes away from the sea, which makes for a great

distance from the hustle and bustle of the tourist-crazed coast. The river Mirna,

which used to bring ships from the sea to this merchant town, has all but evaporated,

and Daytona, as it was called by the Italians, is blissfully removed from the

world.

On either side of the entrance to

the house are two rooms with stone walls which were obviously stores; we heard

that the merchant in this house sold olive oil and flour. These rooms are cold

and were never really used, although they were the subjects of many of our daydreams.

Our mother had so many visions for these rooms that I lost track-her favorite

was of an antique store. But none of them materialized; the rooms are empty

to this day.

I was reading about Agni, the Indian

fire god-the Sun and the Heart of the Sun. Agni is the god who, as fire, receives

the sacrifice and, as priest, offers it to the gods. The element of fire also

pervades the whole universe. The Sun, in the highest heaven, is kindled in the

storm cloud and comes down to earth as lightning where he is ever reborn by

the hands of men. And so we are transformed through fusion with the light, the

Divine light.

Inspired by these images I decided

to do a performance called "Red Angel" and announced to everybody in town that

the show would last for five hours. First I started working on the space. I

painted the walls. One side was dark, with snakes moving toward the ceiling;

it was black, Red and brown. The other wall facing the dark side was light,

the future, and the center had a two-faced bird, looking both east and west;

next to it was a large spiral. Then I took some wooden panels and painted them

silver, with some Hebrew writing that I copied from a record that I borrowed

from Lucia, a friend who comes to Motovun every summer. She sparked off the

whole event in a way. We had one of those Motovun discussions about art, and

I set off to prove something, I don't quite remember what...

I was hanging out with a young guy

during my stay that summer. We were being really wild, like two stones hitting

each other, creating friction. He became part of this Event. I painted an old

chair and wrote "Red Angel" on it, put it in front of the door, as a sign. Then

I filled three stone vessels that had been used a long time ago for olive oil,

with colored water, one Red, another yellow, and the third black. Strange things

were being reflected here-Hebrew writing and a German flag? I don't know what

I was tapping into here; eerie echoes of World War 11?1 painted my whole body

Red. I then wrapped myself in a Red piece of fabric and put on my head a Montenegran

cap I found among our souvenirs in the house. The boy was in charge of the record;

it was to play continuously. The record was of songs of children in a Jewish

ghetto, in Yiddish. I really don't know why it moved me so. We lit many candles

around the room. I struck a pose of a Roman goddess statue and we opened the

doors to the public.

The

first hour was the hardest. I had many thoughts going through my mind, many

distractions from the people who started streaming in.But the worst was controlling

my body. After not too long, my muscles started tensing. I started thinking

that I wouldn't make it through. My mother came in and started panicking that

I was standing on a cold floor bare foot—there go the ovaries! My father was

getting drunk on local Red wine. It was all a challenge to keep from bursting

into laughter. People were talking into my ear, purposely trying to make me

move. And then I suddenly thought: "I'm wearing Red, like the monks, the Buddhist

monks; they meditate for hours without moving. So I will become one of them."

My eyes were half closed, and I moved my sight to a candle flame. Slowly the

sounds of the people surrounding me became a murmur. I visualized Motovun on

top of the hill, and myself the statue standing on top. The warm wind was caressing

my body, my Red garment flowing beautifully. In the distance I imagined how

the river moved when it was in its prime, with Venetian ships calmly flowing.

I looked up at the sun and felt the warmth like a bath of blissful energy. Then

suddenly I felt angels surrounding me, playing with me, touching me with their

Wings. Amorphous, they had no faces, like birds of energy, smiling energy. I

realized that they were communicating to me, that they approved of my action.

Slowly there were more and more of them, creating a spiral around my body and

up, up into the sky towards the center of the Sun. As I descended back into

the space, I heard blurred sounds first; then they became voices and I heard

someone whispering in my ear, "I love you," dropping something into my hands,

which were open and cupped. I closed my hand and slowly opened my eyes. There

was quite a sight in front of me; a pagan get-together had taken place. There

were food leftovers, opened bottles of wine with empty cups. People sat at the

edge of the room comfortably chatting. I had really become like a statue, non-imposing.

It was time to close the doors....

The

first hour was the hardest. I had many thoughts going through my mind, many

distractions from the people who started streaming in.But the worst was controlling

my body. After not too long, my muscles started tensing. I started thinking

that I wouldn't make it through. My mother came in and started panicking that

I was standing on a cold floor bare foot—there go the ovaries! My father was

getting drunk on local Red wine. It was all a challenge to keep from bursting

into laughter. People were talking into my ear, purposely trying to make me

move. And then I suddenly thought: "I'm wearing Red, like the monks, the Buddhist

monks; they meditate for hours without moving. So I will become one of them."

My eyes were half closed, and I moved my sight to a candle flame. Slowly the

sounds of the people surrounding me became a murmur. I visualized Motovun on

top of the hill, and myself the statue standing on top. The warm wind was caressing

my body, my Red garment flowing beautifully. In the distance I imagined how

the river moved when it was in its prime, with Venetian ships calmly flowing.

I looked up at the sun and felt the warmth like a bath of blissful energy. Then

suddenly I felt angels surrounding me, playing with me, touching me with their

Wings. Amorphous, they had no faces, like birds of energy, smiling energy. I

realized that they were communicating to me, that they approved of my action.

Slowly there were more and more of them, creating a spiral around my body and

up, up into the sky towards the center of the Sun. As I descended back into

the space, I heard blurred sounds first; then they became voices and I heard

someone whispering in my ear, "I love you," dropping something into my hands,

which were open and cupped. I closed my hand and slowly opened my eyes. There

was quite a sight in front of me; a pagan get-together had taken place. There

were food leftovers, opened bottles of wine with empty cups. People sat at the

edge of the room comfortably chatting. I had really become like a statue, non-imposing.

It was time to close the doors....

Later, I was told what had transpired.

Tourists passed through and took photographs, posing next to me. Lucia came

in and started crying; it really touched a soft spot in her. I guess I proved

whatever I set out to, which now completely escapes me. And then a group of

friends brought food and wine and sat down to enjoy the show. In my hand was

a rosary, with a Virgin Mary.

I

continued to work with the image of Red Angel in many media. Appropriately enough,

by strange circumstance I ended up having a workspace in a bronze foundry in

Corona, Queens. I was working on a Red Angel installation that traveled to Venice.

The presence of fire was constant.

I

continued to work with the image of Red Angel in many media. Appropriately enough,

by strange circumstance I ended up having a workspace in a bronze foundry in

Corona, Queens. I was working on a Red Angel installation that traveled to Venice.

The presence of fire was constant.

Every time bronze was melted, the

workers knew to call me to watch. Liquid metal being poured; I was witnessing

an ancient alchemical process. One moment hard, the next liquid. One moment

shapeless, the next a face, a body, anything out of our imagination. I made

one bronze during my short stay there, a Wing. Just before it was ready to be

cast, a fire broke out in the workroom. Thanks to one of the workers, it was

saved. It was in wax form at that point, and it would have just melted away.

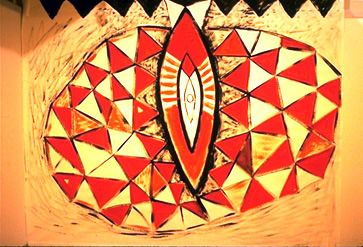

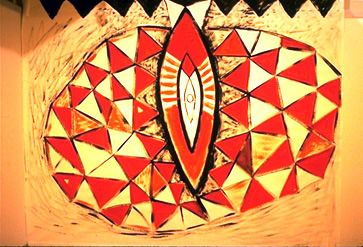

The installation consisted of one

Red sculpture, with the wing; one white sculpture, a ship, egg shaped, on top

of which were found pieces of a shipwreck; and three paintings, two Red and

one white; the white one I named "White Result."

I was in a fiery creative mood there,

but just as soon as the pieces were completed, I lost the space; it was sold.

So once again I was without a workspace and I continued my artwork in a basement

on St. Marks Place belonging to Lawson, a friend and carpenter I've known for

years. It was fine at first, especially since Lawson is such a good craftsman.

He helped me build a Column, a Moon, the Ship and the pedestal for the Wing.

During this period I spent most of the time wearing a gas mask. We used very

toxic materials and in a way they mirrored the surroundings that were developing.

Crack crept into this space, and the situation deteriorated swiftly. Crack keeps

nasty company; pretty soon it became unbearable. This particular smoking ritual

is one of death, destruction and suicide; some very evil spirits are summoned

with its smoke.

The

ancient Greeks reamed much from the Zoroastrian magi, who left no monuments

because they believed in natural powers. Herodotus commented: "The erection

of statues, temples and altars is not an accepted practice among them, and anyone

who does such a thing is considered a fool, because, presumably, the Persian

religion is not anthropomorphic like the Greek. God in their system is the whole

circle of the heavens and they sacrifice to him from the top of the mountains.

They also worship the sun, moon, earth, fire, water, and winds, which are their

only original deities...." Herodotus also mentions the Medean magi, who were

known long before the days of Zoroaster as a magico-priestly caste, one of the

six tribes of Medes. It is from this race of men that the word magic is

derived. To the Greeks, the word rnagia originally signified the religion,

reaming and occult of the Eastern magi. The magi penetrated into Greece, India

and even into China. They transcended religious differences, for there was always

something universal and international about the nature of magic. It was the

descendants of this priestly caste that came from the East to proclaim and worship

the newborn Christ.

The

ancient Greeks reamed much from the Zoroastrian magi, who left no monuments

because they believed in natural powers. Herodotus commented: "The erection

of statues, temples and altars is not an accepted practice among them, and anyone

who does such a thing is considered a fool, because, presumably, the Persian

religion is not anthropomorphic like the Greek. God in their system is the whole

circle of the heavens and they sacrifice to him from the top of the mountains.

They also worship the sun, moon, earth, fire, water, and winds, which are their

only original deities...." Herodotus also mentions the Medean magi, who were

known long before the days of Zoroaster as a magico-priestly caste, one of the

six tribes of Medes. It is from this race of men that the word magic is

derived. To the Greeks, the word rnagia originally signified the religion,

reaming and occult of the Eastern magi. The magi penetrated into Greece, India

and even into China. They transcended religious differences, for there was always

something universal and international about the nature of magic. It was the

descendants of this priestly caste that came from the East to proclaim and worship

the newborn Christ.

The Greeks had a goddess who represented

the priceless life-giving necessity of fire—Hestia. She was the deity of the

hearth, daughter of Cronus and Rhea. In Greek tradition she has almost no mythology;

she is mentioned only in the Homeric hymn to Aphrodite. She refuses both her

brother Poseidon (Water) and her nephew Apollo as consorts, insisting on remaining

a virgin. Hestia is a sacred principle personified and much honored. She kept

apart from the disputes on Mount Olympus, and was represented in the city, which

maintained the public hearth, as well as in the home. She was invoked before

all sacrifices, and colonizers from Greece took fire to their new lands from

their native city hearth, the prytaneia. The Romans continued the practice,

renaming the state goddess of the hearth Vesta.

The Zoroastrian bible was called Avesta; there is a direct connection, a tradition

handed down.

Vesta was also worshipped in every

household. The sacred fire of the state burned in Vesta's temple on Via Sacra,

just below the Forum; it was renewed on March 1st, the first day of the Roman

year (Angelica's birthday). Otherwise it burned perpetually. Her festival Vestalia

was held on June 9th, the day I was born. On that day her beast, the ass, was

given a holiday from labor and decorated with garlands of violets and strings

of small loaves. The storehouse of the temple of Vesta was opened from the 7th

to the 15th of June to enable the Roman matrons to bring their offerings to

the goddess. During this period all public business ceased.

The temple of Vesta in Rome represented

the house and hearth of the ancient kings, and just as the Rex sacorum was a

priest who represented the king, the vestal virgins represented the king's daughters.

They were originally four in number, later six, but always highborn girls from

patrician families. They had a number of duties but were principally the guardians

of the fire of the state hearth in the temple of Vestal. The office was a very

ancient one, older than Rome itself. The vestals were sworn to absolute chastity,

but they could return to private life after thirty years of service. If, during

that time, one was found guilty of breaking her vow, she was buried alive in

an underground chamber near the Colline gate, conveyed there bound hand and

foot in a covered litter. She was made to descend a long wooden stair, which

was then drawn up. (Michael Stapleton, Dictionary of Greek and Roman

Mythology, Peter Bedrick Books, New York, 1986, p. 207, Vestal )

Men who are connoisseurs of smoking

(in the Western world) always relate to their smoking passionately, as if to

a lover. ].M. Barrie's book Lady Nicotine about the pleasures of smoking

says that a gentleman must always use a "Vesta" to light his cigar. They differ

from ordinary matches only in the name, the tradition.

I

don't remember exactly where we were going, but we were in a bus when Shuli,

an artist friend also looking for workspace, told me about this one place I

might consider. A basement, again, but it happened to be in the middle of Soho.

Soho! I never even knew Soho when it belonged to the artists; that was before

my time. The only Soho I knew was of galleries, of trendiness, the very commercial,

very expensive Soho. Shuli also mentioned something about having to pass though

a very strange space. The strange space fumed out to be a cigar factory! It

looked like something out of the 19th century, the exploitation of the workers

in the most miserable circumstances. And that worker was a woman; in fact, only

women worked in this factory. At the entrance one of the workers was beating

the tobacco leaves with great anger in her movements.

I

don't remember exactly where we were going, but we were in a bus when Shuli,

an artist friend also looking for workspace, told me about this one place I

might consider. A basement, again, but it happened to be in the middle of Soho.

Soho! I never even knew Soho when it belonged to the artists; that was before

my time. The only Soho I knew was of galleries, of trendiness, the very commercial,

very expensive Soho. Shuli also mentioned something about having to pass though

a very strange space. The strange space fumed out to be a cigar factory! It

looked like something out of the 19th century, the exploitation of the workers

in the most miserable circumstances. And that worker was a woman; in fact, only

women worked in this factory. At the entrance one of the workers was beating

the tobacco leaves with great anger in her movements.

Daily I passed through, observing

these women, Hispanic women, illegal for sure, smoking as they worked! It was

quite a sight, and the smell—your eyes would water after only a few moments.

There is no way to describe that smell; it is so strong, it hurts.

I was drawn to this factory, to the

women. It was becoming an obsession. I wanted to do something with it, but I

had no idea what. A documentary? Definitely not. But I had to start somewhere,

so I decided to simply videotape the scene. I became familiar with the workers

and the owner of the factory, and when I asked him if it was okay he didn't

seem to mind. So I booked a day for camera and crew.

Two days before the shoot, I

was taken to dinner at 21—the famous 21, where the very famous and very rich

meet. Being the obsessive person that I am, throughout the dinner I discussed

only the cigar factory, how amazing it was to see those women smoking and rolling

tobacco. The image one usually has in mind is of a man smoking a cigar, a fat

boss ordering people around... not women, never women. Why is it o.k. for a

man to suck on a phallic symbol in public?

On our way out we stopped at the

restaurant's cigar stand. All this talk about cigars made my date want to light

one up. And there was this beautiful Latin girl, Emilia Cleopas, the cigar sales

girl. We started talking, and she spoke with such knowledge and passion about

cigars, I immediately invited her to the video shoot for an interview.

When we arrived at the factory for

the shoot, everything seemed fine. We set up the camera and lights and started

to videotape. The next moment there was a rising tension in the air; we began

to feel uncomfortable. The women started protesting, hiding their faces. Finally,

the factory owner came out and said: "Victoria, I'm sorry. Next thing you know,

they'll ask for a raise in pay and all kinds of bullshit."

I felt like an aggressor; the camera

had become like a gun being pointed at them, the lights as if for interrogation.

They were clearly frightened; frightened and angry. Angry because somebody had

told them that across the street there is a man who makes a lot of money with

video—Nam June Paik. They felt I was manipulating them, and I felt that they

were manipulated enough, so we retreated to the basement. We waited for the

cigar sales girl from 21.

When Emilia finally showed up, she

was all geared up to start her talk. I had only one request, to paint her lips

Red. She sat down and calmly gave a startlingly beautiful monologue about her

experience of the cigar. She opened up a whole now dimension about this most

male symbol in Western society—the phallic symbol itself. At 21, where she worked,

successful, rich men met and made deals. She felt that when they smoked the

cigar, they were practicing magic. Were they aware of that? Back in her neighborhood,

the people who smoke cigars are very religious people, and more often than not,

women. She smoked a cigar while she talked. It was very sensual the way she

sucked on it—slowly, like a good lover, taking her time.

Emilia

personified the modern age Carmen to me, especially in this setting. In the

cigar factory she looked as if she belonged, and as if she came from another

planet. She said that Santeristas would puff cigar smoke into a bowl of water

and see your past, your future. Tobacco smoke is a very powerful medium.

Emilia

personified the modern age Carmen to me, especially in this setting. In the

cigar factory she looked as if she belonged, and as if she came from another

planet. She said that Santeristas would puff cigar smoke into a bowl of water

and see your past, your future. Tobacco smoke is a very powerful medium.

According to Emilia, loving to smoke

a cigar has nothing to do with penis envy. Women in South America smoke cigars,

and not much is thought of that. This is their way of reclaiming the power,

through the magic powers of smoke. At 21, men smoke a cigar after a multi-million

dollar deal, but she smoked to come closer to God. She said that there are two

Gods, the spiritual and the material—the Eastern and the Western. How she views

these men at 21 is particularly interesting. They smoke a cigar while they are

making a business deal because it allows them to see through the person they

are negotiating with. Is it possible that modern businessmen are tapping into

the archaic magic practices?

Bizet's Carmen worked in a cigar

factory. The thought of all those women together in the tropical heat, half-dressed,

rolling the cigars on their thighs must have inspired the opera. The smoke,

she sings, is elusive, like love, you cannot hang onto it.... Women are almost

always the workers in the factories; we are reminded that they are the creators

of the phallus.

Emilia thinks that men are intimidated

by women who smoke cigars. We are all so unaccustomed to this sensual sight.

I asked her to tell more about the religious aspect of smoking. Every Monday

morning when she woke up she smoked a cigar, to start her week.

And the ritual went like this: "I

light all my candles, and at the end of my prayer, I light the cigar. Instead

of inhaling it, I put it in my mouth and I blow out; that's the way you communicate

with the saints, 'cause the saliva is on it and all your thoughts are on it,

too. When I'm in deep thought, I smoke a cigar. When you die, your body leaves

in a puff of smoke. I guess it's like smoking a cigar." The Buddha come pared

rebirth to the lighting of a new candle from the flame of a dying one. The flame

goes on, but the candle or the body is consumed. In the "Voice of Silence,"

a Tibetan Buddhist text, it is said: "Out of the furnace of man's life and its

black smoke, winged flames arise, flames purified, that weave in the end the

fabric glorified of the... vestures of the Path." The cigar is never put out,

but the glowing spark is left to die. Emilia continued: "The cigar is very sacred

in Santerismo. It is the only way really to talk to the saints. Anything you

want to ask them, you ask through the cigar. All the women smoke cigars, all

the disciples. Santerismo is the oldest religion on earth. It comes from Africa.

Smoking a cigar is pure; it is a sign of power."

I had no knowledge of Santeria and

asked her to elaborate. I understood her saying that its roots were in Africa,

in Uruba. She didn't know the spelling or much else about it. But she was certain

that it was the oldest religion on earth. "Anytime I want to know anything abut

a person and their life, I smoke a cigar, and I'm able to see through them like

glass. Maybe that's why when I walked in here [the factory] all the women smiled

at me. I guess they knew deep down who I was."

Who was she? She came as an answer

to the undefined question I had about the women in the factory, the feelings

I got. She opened the door I was looking at; not the history of cigars, or the

different names and makes. I wasn't interested in the accepted facts; I wanted

the woman's point of view, the deeper truth, the ritual.

Right after this I was invited to

do a performance at a gallery in Soho. A few friends and I smoked cigars, including

Emilia, whose video was projected in the background on a large screen. The images

and the smoke offended the owners and we were kicked out.

My

then future husband Bogdan and I went to California to conduct an interview

with his colleague, Murray Gell-Mann, a Nobel laureate and the discoverer of

quarks. I asked him if he knew where Urubas were and he corrected me: Yoruba,

in Nigeria. In fact, his interview began with him pointing to a Yoruba divination

bowl, which he jokingly said physicists need in order to make discovcries.

My

then future husband Bogdan and I went to California to conduct an interview

with his colleague, Murray Gell-Mann, a Nobel laureate and the discoverer of

quarks. I asked him if he knew where Urubas were and he corrected me: Yoruba,

in Nigeria. In fact, his interview began with him pointing to a Yoruba divination

bowl, which he jokingly said physicists need in order to make discovcries.

The Yoruba culture was quite advanced

when the white man started taking them captive in the 17th century to be their

slaves, they were organized in a series of kingdoms and had a complex social

structure. THe most important kingdom was Benin. Their most important city to

this day is lle-lfe, which according to their legend was created by Orisha Obatala

and is the origin of all that exists. From this powerful culture, they left

behind a rich legacy of art. Almost every piece of African art that I found

exe traordinary came from Nigeria, from the Yoruba tribe. The most fascinating

part of their culture is the mythological aspect, the religious beliefs and

practices. But that I found out later, definitely not from the books in the

library. The material I found there was dry, studious and lacking in explanations

of the rituals and magic.

In the beginning of the 17th century,

the Ewe tribes invaded Yorubaland, forcing the Yorubas to migrate to the Nigerian

coast, where many of them were captured by slave traders and brought to the

New World. Their white masters

felt threatened by their strange worship of deities, and forbade them to practice

their religion. They were forced to accept Catholicism, and accept they did.

Except that instead of the Catholic religion absorbing the African, it happened

the other way around. The African religion was much stronger, because it is

rooted in Mother Earth, in Nature. So the slaves outsmarted their white masters

by hiding their Orishas behind the ""front" of Catholic saints. They appropriated

with time many customs from their new home, but their roots were never lost.

And just as the religion would become less African, a new boat of slaves would

come in and refresh their memory.

There are also theories about the

connection of the Yoruba to Egypt. Some Egyptians migrated to Nigeria looking

for fertile land next to water. They taught the natives there their religion

and showed them how to craft sculptures and pottery. Over time Yoruba evolved

to the form it has now, reaching its peak in the thirteenth century.

There are some 4,000 Orishas (deities)

in the Yoruba pantheon; it resembles the complex pantheon of the Egyptian Gods.

In their human portrayal we are reminded of the Greek Gods. It is all connected--after

all, Africa and Mediterranean Europe aren't that far away. Western historians

arrogantly assume that Africans didn't mix much with the Classical cultures,

and appropriate the glories of Egypt's past as if a completely different race

were in question.

While

immersed in images of Africa, with a map of the continent above my kitchen table,

I got an editing job for a woman who was working on an educational video about

AIDS in Africa. After this session, a dancer booked time with me in another

editing room. When we walked in, the room was still occupied. At the monitors

was a girl dressed all in white, and on the screens was... Africa. She excused

herself for running overtime. I asked where the footage was from. "Nigeria,"

she said. Nigeria! Then I asked her if she knew anything about the Yorubas.

She responded: "These are Yoruban rituals that I videotaped." We started talking,

much to the dismay of the dancer waiting for me, but this was what I was searching

for. I told her about Emilia. She asked if she was a priestess. I had no idea;

the thought had never occurred to me. I asked her to write down her telephone

number and next to the number she wrote "Basha Alpern, Yoruba priestess."

While

immersed in images of Africa, with a map of the continent above my kitchen table,

I got an editing job for a woman who was working on an educational video about

AIDS in Africa. After this session, a dancer booked time with me in another

editing room. When we walked in, the room was still occupied. At the monitors

was a girl dressed all in white, and on the screens was... Africa. She excused

herself for running overtime. I asked where the footage was from. "Nigeria,"

she said. Nigeria! Then I asked her if she knew anything about the Yorubas.

She responded: "These are Yoruban rituals that I videotaped." We started talking,

much to the dismay of the dancer waiting for me, but this was what I was searching

for. I told her about Emilia. She asked if she was a priestess. I had no idea;

the thought had never occurred to me. I asked her to write down her telephone

number and next to the number she wrote "Basha Alpern, Yoruba priestess."

It wasn't easy getting a hold of

Basha. I tried calling many times; she lived in a hotel uptown on Broadway.

I was never sure if she got the messages. Finally one day I got a booking for

editing and it fumed out to be with her. She required titles over her Nigerian

footage. So I learned in the process the names of different dances, rituals,

cities.... Basha lived part time in Nigeria and worked for the king(! ), videotaping

his family and social affairs. Occasionally she herself would appear in the

video, and it was guise a sight. A white woman (of Jewish background) dressed

all in white, in the middle of Africa, a Yoruba priestess. I wondered how she

got there. Through the drum, she said. She played the conga drum, started following

the history of the drum. "When you follow the history of the drum, you find

the history of the people."

The tape I was helping her with turned

out robe for a panel discussion she was organizing, on the Yoruba culture. When

she asked me to videotape the event, I knew that I was coming closer to the

real story. The guests were Baba Afolabi Epega, a Nigerian babalawo (high priest

of Yoruba), Adeyemi Bob Thomson, an African-American practitioner, and

Beatrice Morales Cozier, an anthropologist

from Cuba. Throughout the discussion, Bob Thomson thoughtfully smoked a cigar.

Earlier I had approached him and asked about the connection, but he quickly

dismissed me. ("You silly girl.")

I started asking myself how all this

connected with the cigar factory, with those women. I was wondering if I was

losing sight. Towards the end my frustration grew apparent and there ensued

a long dialogue between the panelists and myself at the camera. My first question

referred to the book I was reading connecting the Yorubas to Egypt. The response

was that it was the other way around; that Egypt assimilated the Yoruba culture;

that lle-lfe is the beginning of mankind. I dared to ask what the importance

of women in the rituals is and also about the fact that in Nigeria polygamy

is commonplace. This seemed to really create some disturbance in the room. The

babalawo was especially perturbed. He asked me if I knew where my husband was,

trying to point out that when a man has more women they know exactly who he's

with. I was unhappy with the direction all this was taking and finally directed

a question to Beatrice Morales about women and cigars. Bob Thomson made a joke:

"Please help her; she's been asking this question all day." I knew she was the

one who could help me out of this impasse. And she was. She didn't act as if

it were a far-fetched question, didn't avoid the subject, but proceeded to talk

about women in the 16th and 17th centuries who were merchants of tobacco. She

had to cut the answer short because it was going away from the subject that

they had met there for, but in Beatrice I knew I had found the right person

and was determined to continue our discussion. Immediately after the panel meeting

I asked her for an interview. It wasn't easy, since the people running the place

were anxious to get us out. So I climbed out onto the terrace with the camera

person and set up lights. We shot a ten minute interview, until they kicked

us out of there, too. It didn't look like I was going to be able to continue

at another time because she lived in New Orleans and was very busy finishing

her dissertation in Cuban anthropology. Here are a few things she said at our

first encounter:

One of the things that's

important in the history of tobacco is the role of women. The period you

were probably looking at is the 19th century; the period I am talking about

is the 16th century. So imagine the conditions. There were very few European

women in the Caribbean. It was composed of people working for the crown,

the settlers who came without women and made it with the African women,

the Congolese and the Indians over there, the Tainos we call them. The Tamos

blended in and disappeared as a race, but their culture did not die. They

passed on their culture to the next group of people who came to work there,

the Africans.

And the tricky part is to

understand how these women managed to run their businesses under such a

tremendous condition of domination. It also might give us a different picture

of how sexuality was used. These women were not married women, and they

were classified during Christian times as prostitutes. They had various

lovers—the story of women and their many husbands. That's part of the hidden

story. So we only get an idea of these women looking at the mythology of

female divinities and their lifestyle. That puzzled me. I asked why is it

that Oshun is so independent and all of the Orishas have these qualities

and they are being classified as prostitutes? But they were being judged

from a very Christian perception of things which gives women very little

flexibility. It puzzled me that women were selling tobacco not only in Cuba

but also in the Dominican Republic, which had a big tobacco industry. They

were networkers.

At that point we were rudely interrupted

by the person in charge and ordered to stop and get out. I begged for only five

minutes more and he agreed "Five minutes!" "Thank you," I said and turned to

Beatrice to go on.

What you just did is exactly what

I am talking about. Subordination. The way you just appealed to get your objective,

to reach you goal. These women were marked in literature as prostitutes, thieves,

women of the world. But I think, between us, and I don't know how open I want

to be about this, that they were the backbone of religion. Because I think

that the Ifa priest came very late, to bring this superiority, patriarchy,

which is what is claimed to have maintained the religion. And tobacco gave

them an ability to buy their freedom. The Spanish brought with them an institution

called Cortasion, which they borrowed from the Romans. The slaves were treated

like human beings, not like later in the 19th century. You were a human being,

a persona, and you could buy your freedom and also marry to freedom.

And the women were using this to the fullest extent!

This insight changes history

because of the fact that we don't see women as making decisions; we don't

see woman as actors in history. So when you begin to look at Cuban history

you see all these institutions that we see now and that we are so proud of,

that Africans were able to retain in the New World. If you were to find the

hidden character, the contribution, you would find that the women are right

there. And I think that's the lead to follow, to uncover. Just like when we

uncover the history of Afro-Cubans we have to pay attention to the role of

women and tobacco. Without concentrating solely on women, the tobacco allows

you to discover the hidden actor. I think that is something we can continue

to uncover as we do more work.

She concluded hastily as the man

once again appeared, this time determined to get us out.

All

this reminded me of something that happened nine years ago. It was a very hot

and humid summer. I lived on Seventh Street between B and C. I went out to get

some groceries. At St. Marks Place I stopped and browsed around at what was

being sold on the street. Lots of junk, as usual, hot bicycles and other wares.

And there, in the middle of the chaos was sitting a young man, clean shaven,

dressed in black. In front of him on the pavement was a piece of blue velvet

on top of which were three or four religious pieces. I bought a silver cross

from him and left. On my way home I heard some Latin music and singing from

a small church. There was a man standing at the door. I wanted to take a peek.

He said: "Come in, come in." I stepped in. A young girl with a pretty face in

a white lace dress approached me. She said "I will translate to you; I will

be your Guide." She took me by the hand and sat me down, next to her. I was

enjoying the music, singing with percussion, congas and guitars. It was wonderful.

I turned to the girl and told her that it gave me shivers how beautiful it was.

She said that meant I was in the presence of God, then got up, went to the front

and whispered something in the priest's ear. Then the priest came to the microphone

and spoke. People started turning around and looking at me. His speech became

more and more passionate, he pointed at me. The priest said that he had a message

from God and that I was sent to them to be purified from Sin. He asked me to

step to the altar. I had no way out, so I proceeded. I came to the front, he

told me to lean down. A woman was on the other side of him. They laid their

hands on me and started screaming for the Devil to come out. Then they started

playing a rhythm on the drums and chanting I looked to the left, to the right;

people were turning in circles like dervishes, going into a frenzy. A woman

was crying. They poured water on the ground, on me. Then, slowly everyone settled

down. I gave the cross I had bought earlier to the girl, excused myself, took

my groceries and left. As I crossed the street to my door, put the key in, a

torrential flood of rain suddenly descended. This sent a chill through me; I

ran up all six flights of stairs in one breath. When I walked in my lower body

was covered with blood.

All

this reminded me of something that happened nine years ago. It was a very hot

and humid summer. I lived on Seventh Street between B and C. I went out to get

some groceries. At St. Marks Place I stopped and browsed around at what was

being sold on the street. Lots of junk, as usual, hot bicycles and other wares.

And there, in the middle of the chaos was sitting a young man, clean shaven,

dressed in black. In front of him on the pavement was a piece of blue velvet

on top of which were three or four religious pieces. I bought a silver cross

from him and left. On my way home I heard some Latin music and singing from

a small church. There was a man standing at the door. I wanted to take a peek.

He said: "Come in, come in." I stepped in. A young girl with a pretty face in

a white lace dress approached me. She said "I will translate to you; I will

be your Guide." She took me by the hand and sat me down, next to her. I was

enjoying the music, singing with percussion, congas and guitars. It was wonderful.

I turned to the girl and told her that it gave me shivers how beautiful it was.

She said that meant I was in the presence of God, then got up, went to the front

and whispered something in the priest's ear. Then the priest came to the microphone

and spoke. People started turning around and looking at me. His speech became

more and more passionate, he pointed at me. The priest said that he had a message

from God and that I was sent to them to be purified from Sin. He asked me to

step to the altar. I had no way out, so I proceeded. I came to the front, he

told me to lean down. A woman was on the other side of him. They laid their

hands on me and started screaming for the Devil to come out. Then they started

playing a rhythm on the drums and chanting I looked to the left, to the right;

people were turning in circles like dervishes, going into a frenzy. A woman

was crying. They poured water on the ground, on me. Then, slowly everyone settled

down. I gave the cross I had bought earlier to the girl, excused myself, took

my groceries and left. As I crossed the street to my door, put the key in, a

torrential flood of rain suddenly descended. This sent a chill through me; I

ran up all six flights of stairs in one breath. When I walked in my lower body

was covered with blood.

I never had an explanation of what

transpired that day. But now I was getting an inkling. Certainly it wasn't a

purely Christian affair. It was more like a shamanistic ritual. It must have

been a Santeria church that I walked into.

Santeria is not confined to the ignorant

and the uneducated. Some of the people I met who are followers of the cult are

real intellectuals. There are some 100 million practitioners of the cult in

Latin America and the U.S., and that is a conservative estimate. In Cuba, where

Santeria has developed extensively, the Yorubas are known as lucumi This

term is derived from the Yoruban word Akumi, which is the name given to a native

of Aku, a region of Nigeria where a lot of the Yorubas come from. The Cuban

lucumis were influenced by the Catholic imagery, although the essence of the

religion is purely African. I was delighted to have met Beatrice. She was from

Cuba and an anthropologist! At the panel meeting she said that her mother, Rosa

Levya "Shango Laramie," was a priestess, and many times wanted her to become

one too. She resisted, saying that she was interested in anthropology, to which

her mother responded that there is no difference, and that one day she would

have to face her destiny. It was her mother who initiated Basha into the Yoruba

religion.

The ceremony of initiation was renamed

asiento in Cuba, a Spanish word which means seat. The choice of this word may

be explained by the fact that the saints are believed to take possession of

their initiates and literally "mount" them. The santera is commonly known as

the "horse" of the saints. It is almost identical in the Voodoo religion. During

the initiation, the mind is conditioned for its future work. One is initiated

into the mysteries and rites of the particular Orishas who are recognized as

the "Mother" and the "Father."

When Castro came to power, many

Cubans fled the country, bringing with them the African rituals and magic. Soon

it spread throughout the South, particularly New Orleans and Miami, as well

as New York and New Jersey. Who would believe that the city that symbolizes

the height of civilization and modernity has so many practitioners of this cult!

But in New York you can see numerous botanical, which are the centers for practitioners.

These stores were opened by women originally, and they are where you can purchase

your candles and potions. And for a fee, it can be arranged for someone to cast

or rid a spell. Sometimes it is quite costly, all depending on the seriousness

of the situation at hand.

The

Havana cigar is considered by connoisseurs to be the creme de la creme. It has

been a forbidden fruit since 1959, when the U.S. put an embargo on Cuban tobacco.

And the symbol of the capitalist world, many times seen in Communist caricatures,

suddenly became readily available in the Soviet Union. And so Cuban magic traveled

to Russia. Meanwhile Castro recently received an award from the United

The

Havana cigar is considered by connoisseurs to be the creme de la creme. It has

been a forbidden fruit since 1959, when the U.S. put an embargo on Cuban tobacco.

And the symbol of the capitalist world, many times seen in Communist caricatures,

suddenly became readily available in the Soviet Union. And so Cuban magic traveled

to Russia. Meanwhile Castro recently received an award from the United

Nations for quitting the cigar! Many

Cubans believe that Castro owes his success to the black magic of the Cuhan

mayomberos (witches). It is rumored that the African deities placed him

in his position of power. In fact, quite a few dictatorships in Latin America

have been credited to works of magic. Only recently, when Noriega fled from

the U.S. troops, they found remnants of a magic ritual in his room. Animal parts

candles, offerings. And the New York Ames reported that he always wore

Red underwear as a means of protection.

Cuba has a peculiar history owing

largely to its geographical placement. Less than 90 miles from the Florida Keys,

it commands the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico and the Panama Canal. Now that

Noriega has been ousted and the Soviet Union has gone broke, it finds itself

isolated. The Indians who inhabited the island at the time of Columbus's landing

possessed no written language and because they were peaceful were annihilated

or absorbed, or else died out. At least three cultures swept through the island

before the arrival of the Spaniards: the Guanahatabeyes, the Ciboneyes, and

the Tainos, whom Beatrice mentioned earlier.

Most is known of the last group.

They had a rather advanced economic system based on agriculture. Tobacco, cotton

and corn were the most important part of the economy. The Tainos believed in

a supreme invisible being and their religion was idolatry. Ancestor worship

was common and they carved idols that resembled their ancestors. Tobacco was

used for smoking as well as for religious ceremonies and for curing the ill.

There was almost no mingling of races between the Spaniards and the Indians.

But the black slaves did have contact with the Indians. After all, their cultures

weren't that far apart from one another. They both worshipped nature, above

all, and their ancestors. Beatrice Morales spoke about this connection.

Emilia's Monday morning cigar-smoking

was a reenactment of an ancient Indian ritual. Beatrice translated a description

of the ritual from Spanish:

The rebel Indians communicated with

their ancestral warriors by keeping their bones in a clay pot and smoking tobacco;

this pleased the ancestors and ensured victory. One of the most interesting

rituals in the Afro-Cuban spiritual houses is the peculiar way in which the

mediums smoke tobacco. The Afro-Cuban medium, and all the spiritistas, place

the lit part of the cigar in their mouth, and they inhale the smoke in this

way, without breathing or opening the mouth. At the stream end of the cigar,

which is not lit, they exhale the smoke which reaches out into a fine, beautiful

line and leaves a trail of aroma in the air, covering the room. And thus they

sit in a circle. The tobacco ritual prepares the environment so that the group

can transcend their everyday world. The power of culture is amazing. In the

same way, we can see that tobacco was being smoked 500 years ago by the indigenous

people in the Caribbean. This ritual was passed on to the Afro-Cuban women who

were the traders of tobacco. Some people believe that tobacco is symbolic of

the AfroCuban culture. It's a combination of strength; and it's composed of

different cultures—the AfroSemitic culture, which goes back to the 13th and

14th centuries when the Moors, Africans, Jews, and Gypsies formed a minority

in Spain. We know that there was a lot of cultural assimilation going on when

they came to Cuba in the 15th and 16th centuries....

The

Yoruba tradition, as well as the Indian, was written down for the first time

when it came to Cuba. Familiar symbols began to emerge as I read about Shango.

Shango is a storm deity of the Yoruba. Each town or village in Nigeria has its

own Orisha who acts as a patron saint and protector of the people. Shango is

worshipped in the city of Oyo. This divinity was once a king, a strong ruler

and a great doctor. But he was also tyrannical. He could kill people by breathing

fire from his mouth.

The

Yoruba tradition, as well as the Indian, was written down for the first time

when it came to Cuba. Familiar symbols began to emerge as I read about Shango.

Shango is a storm deity of the Yoruba. Each town or village in Nigeria has its

own Orisha who acts as a patron saint and protector of the people. Shango is

worshipped in the city of Oyo. This divinity was once a king, a strong ruler

and a great doctor. But he was also tyrannical. He could kill people by breathing

fire from his mouth.

There are different versions of the

story of how Shango fled to the forest and eventually hanged himself. But all

agree that the place of this tragic event was Koso. This shameful event was

mocked by his enemies and they cast scorn on his name. So his friends contacted

a great magician who summoned a series of thunderstorms, causing the devastation

of the city of Oyo. His followers immediately proclaimed that the storms were

caused by Shango's anger. Many sacrifices were made in his honor and his followers

to this day proclaim "oba ko so," meaning ""the king did not hang himself."

In New Oyo, the central shrine is

the palace of the king Alafin, who is said to be a direct descendant of Shango.

His symbols are his mortar, in which he prepares the thunderbolts; his magic

spell; his castle; and a double-edged axe, which is usually made of wood, painted

in Red and white and covered with cowrie shells. His colors are Red and white

and his numbers are four and six. He is the patron of the firemen. He is invoked

in works of dominion, passion and many other endeavors.

All of the legends and the central

theme of Shango are based on power, be it procreative, de-. structive, medicinal

or moral. The power is materialized in Shango's staff, which generally depicts

a woman with a double-edged axe on her head. Thunderbolts are called thunder

axes and are said to fall on the ground whenever there is a storm. Many double-edged

axes are found in the Mediterranean world also. The Yoruba compare the noise

of thunder to the bellowing of the ram, and these animals are sacred to Shango

and wander freely about the marketplaces. He is propitiated with apples, bananas,

roosters, cigars, and on special occasions with the ram himself. At the mention

of his name, his followers lift themselves off their seats in a show of respect

for the electrifying Orisha.

The shrines of Shango in Oyo have

a collection of thunderstones which preserve the power. These are collected

by his priests from houses that are hit by lightning. The thunderstones are

kept inside a wooden bowl which sits on a tall mortar (pilon) know as

odo Shango. On the Orisha's festival the odo is washed in water containing the

crushed leaves of several plants, the juice of a snail and palm oil. Then a

rooster is sacrificed and the blood poured over the thunderstones. Later the

blood of the ram is poured over the stones. These African practices have been

preserved nearly intact in Santeria.

Saint

Barbara is Shango's syncretization. She was identified with Shango because she

has a cup in one hand (Shango's mortar), a sword (his axe) in the other, and

a castle at her feet. Her mantle is Red, her tunic white, and she is associated

traditionally with thunder and lightning. She is also the patroness of artillerymen.

Once again, a virgin and a martyr. Her legend dates back to the 7th century.

She was the daughter of Dioscorus, who kept her beauty guarded. When she professed

Christianity to her father, a pagan, he was so enraged that her ordered her

to be tortured and beheaded. Dioscorus himself performed the execution, and

on his way home was struck by lightning and reduced to ashes. She is venerated

as one of the 14 Auxiliary Saints, the Holy Helpers, and is invoked in thunderstorms.

Saint

Barbara is Shango's syncretization. She was identified with Shango because she

has a cup in one hand (Shango's mortar), a sword (his axe) in the other, and

a castle at her feet. Her mantle is Red, her tunic white, and she is associated

traditionally with thunder and lightning. She is also the patroness of artillerymen.

Once again, a virgin and a martyr. Her legend dates back to the 7th century.

She was the daughter of Dioscorus, who kept her beauty guarded. When she professed

Christianity to her father, a pagan, he was so enraged that her ordered her

to be tortured and beheaded. Dioscorus himself performed the execution, and

on his way home was struck by lightning and reduced to ashes. She is venerated

as one of the 14 Auxiliary Saints, the Holy Helpers, and is invoked in thunderstorms.

The Santeria cult, like Voodoo, is

frightening to a lot of people because it deals with our primitive, archetypal

feelings, something that many of us have lost touch with. But any religion,

cult, or philosophy can be equally dangerous, depending on how we empower it

with our thoughts.

Every

day I went down to the basement and worked with tobacco leaves and wood. I was

working on an installation at P.S. 1, which was to open on January 9th, my grandmother's

birthday. It consisted of six large objects, covered with tobacco leaves, with

videos inside, interviews with three women: Emilia, the artist, Basha, the priestess,

and Beatrice, the anthropologist. Through their stories I would present a completely

different viewpoint of the cigar and tobacco, the woman's point of view.

Every

day I went down to the basement and worked with tobacco leaves and wood. I was

working on an installation at P.S. 1, which was to open on January 9th, my grandmother's

birthday. It consisted of six large objects, covered with tobacco leaves, with

videos inside, interviews with three women: Emilia, the artist, Basha, the priestess,

and Beatrice, the anthropologist. Through their stories I would present a completely

different viewpoint of the cigar and tobacco, the woman's point of view.

But December was approaching and

I hadn't succeeded in setting up an interview with Basha or Beatrice. It was

as if they were avoiding me. They probably didn't know what to make of my interest

in the subject; generally there is a strong suspicion of outsiders of the religion.

The Yoruba religion is composed of an intricate system of rituals and ceremonies

which are usually performed in the forest; it is a nature religion. There was

a great deal of persecution from the white masters, so the slaves were forced

to surround their religion in a cloak of secrecy. This secrecy, which never

existed in Nigeria, still exists today, and I was experiencing it.

I met with Basha to discuss the possibility

of an interview and she told me that there were a lot of racial tensions and

she was afraid she might aggravate the situation. When the Cubans came to America

with their religions, many Afro-Americans rediscovered their religious heritage,

a religion of their own, not imposed by the white man. And here was a white,

Jewish woman, a priestess of Yoruba! And not to mention that she worked for

the king of Nigeria on top of it all. When Basha realized that I was pregnant,

she opened up to me, and told me that she had been I wanted a child desperately

and had been trying for awhile. Beatrice Morales, on the other hand, lived in

New Orleans, and was very busy with her dissertation, besides having three small

children to take care of. But she told me that she might find some time when

visiting New York. So there was a remote chance.... I was in the last trimester

and my stomach was bulging. One time in the subway, while reading about Santeria

I came across this: December 4th millions of followers honor Shango

and Santa Bar bare. Suddenly everything fell into place. Shango, Cigars and

Women. I had less than a week! I ran to the first phone and called Basha, asking

if we could arrange the interview on Shango Day in the cigar factory. For the

first time she showed some enthusiasm, saying that she had thought about it

and decided to do it, but that she would talk about the sacred drums and introduce

herself as a musician. My excitement grew when she told me that Beatrice was

coming to town the following day, and that she probably would like the idea

of doing the interview on Shango Day. After all, her mother was a priestess

of Shango. December 4th was a Sunday, which was the only day of the week that

the factory was empty all day. Basha decided to organize a small celebration

and got her group together, Grupo Ore-lre. Before they all arrived she called

and asked if I could bring Red and white flowers, some candy, a cup of coffee,

green bananas, and rum. I obliged. They brought their drums, talked about the

bata drum—the sacred drum—and made a libation. Beatrice Morales came a little

later and gave a beautiful talk about Shango, women and cigars. I felt that

the goddess of thunder had smiled.

I

was walking barefoot on a dusty road somewhere in India, for days and days.

Exhausted, I arrived at an ancient temple at the steps of which was a monk.

I approached him, asking for directions; he didn't respond. A young girl came

up to me and said that he was in deep meditation and in another reality, he

couldn't hear me. I decided to go in and drink some water. As I passed the monk,

he opened his eyes and pointed at me: "She, she is the sacrifice." Terrified,

I started to run away, through the temple, into the garden. There was suddenly

a group of them behind me, chasing me like an animal. I ran desperately, approached

a small ruin of a house, ran through it, out the back door, again to a garden.

There I saw high stone steps, covered with moss. The stairway to heaven. I started

the long, long climb. There seemed to be no end. I was surrounded by beautiful

tropical greenery. I climbed and climbed, gasping for breath. When I reached

the top, on the last stair was the Woman. She was so ancient, transparent, dressed

in white. Her eyes were open, but she seemed to look right through me. I pleaded

with her: "They are right behind me, please help me, they want to sacrifice

me." She didn't respond, didn't move. I was desperate, how do I reach her, which

language does she speak. A lightning flash went off and I understood that not

words but only thought could save me.... I woke up in panic. Sacrifice, sacrifice.

The contact between us and God is enforced with sacrifice. This is how we receive

power. All ancient people have sacrificed first humans, then animals, finally

food. Now we reach a point of self-sacrifice. But 1, myself, must make that

decision; no one is allowed to put me to the stake.

I

was walking barefoot on a dusty road somewhere in India, for days and days.

Exhausted, I arrived at an ancient temple at the steps of which was a monk.

I approached him, asking for directions; he didn't respond. A young girl came

up to me and said that he was in deep meditation and in another reality, he

couldn't hear me. I decided to go in and drink some water. As I passed the monk,

he opened his eyes and pointed at me: "She, she is the sacrifice." Terrified,

I started to run away, through the temple, into the garden. There was suddenly

a group of them behind me, chasing me like an animal. I ran desperately, approached

a small ruin of a house, ran through it, out the back door, again to a garden.

There I saw high stone steps, covered with moss. The stairway to heaven. I started

the long, long climb. There seemed to be no end. I was surrounded by beautiful

tropical greenery. I climbed and climbed, gasping for breath. When I reached

the top, on the last stair was the Woman. She was so ancient, transparent, dressed

in white. Her eyes were open, but she seemed to look right through me. I pleaded

with her: "They are right behind me, please help me, they want to sacrifice

me." She didn't respond, didn't move. I was desperate, how do I reach her, which

language does she speak. A lightning flash went off and I understood that not

words but only thought could save me.... I woke up in panic. Sacrifice, sacrifice.

The contact between us and God is enforced with sacrifice. This is how we receive

power. All ancient people have sacrificed first humans, then animals, finally

food. Now we reach a point of self-sacrifice. But 1, myself, must make that

decision; no one is allowed to put me to the stake.

It seems that the most disturbing

fact to Western people about Yoruba and Santeria is the aspect of sacrificing

animals. And yet, if you think about it, we participate in a much more horrendous

mass sacrificial rite. Millions of domestic animals are kept in the most uncivilized

cages and slaughtered with no emotion. We do not see and therefore do not accept

the fact that we are part of this sacrificial rite. Much blood is spilled daily,

for our Big God—material wealth. I am not coming to the defense of the reality

of crime and violence that is connected to the Santeria cult; many drug dealers

are worshippers, and summon the protective powers of the African deities. However,

what is frightening and repelling to us Westerners is the simplicity, the bluntness.

I set up the tobacco installation

and shortly thereafter gave birth to Angelica. She was two weeks old when it

was taken down. It is as if this whole project had a note of fertility ringing

through it. Basha got pregnant, finally. She told me that the conception took

place right around the Shango Day celebration. And throughout this childbearing

year, the landlady of my studio was desperately trying to get pregnant. Forty

and single, she came across some terrible barriers. The time of her ovulation

was invariably a time of crisis in the studio. The frozen sperm was being Federal

Expressed from California, and it had to arrive just at the precise moment.

Once, my mother stayed at the loft for a while, and then my tall, dark and handsome

brother moved in. He had had a fight with his wife. My landlady ape preached

him, and said he could stay provided he donated some sperm. I don't know how

he responded, but after that incident I was handed papers from the lawyer to

terminate my lease, stating that this was a strictly commercial property. Everything

was straightened out eventually; my landlady adopted a beautiful baby girl after

all the struggle. It is as if the childbearing urge became contagious; everyone

around me was having babies all at once. I was passing out cigars like mad.

Angelica turned one and I traveled

to Cincinnati to do a performance. Upon my arrival at the hotel where I was

to stay, a large group of Yoruba drummers stood at the entrance. They too were

guests that day. I took this as a sign that I was not losing my way, and felt

sure of myself while performing that night in front of a handful of people.

I am neither an anthropologist nor

a priestess. Like Emilia I am in between these two worlds: the artist, the messenger.

With the cigar and lightning I made a journey, from the Golden Leaf cigar factory

in Soho to Nigeria, Cuba, Spain, Greece, Serbia and back. And I decided to create

my own myth in the end, the story of the beginning of the World. In the end,

I deliver my own story of the beginning.

In

the beginning there was a Woman. She created the World first in her Mind, then

through her electrical body. Her favorite place for meditation and creation

was on top of mountains that today we call the Himalayas. Her skin was transparent.

milkywhite, all the veins could be seen clearly. She had blue blood flowing

through. Her World was still. As She, the goddess Earth, created the seas, lakes,

rivers and oceans, the mist entered her pores and she had a terrible urge to

push. Through her third eye, millions of pearls were released, each of which

fumed into a different creature as it touched the Earth or the Waters.

In

the beginning there was a Woman. She created the World first in her Mind, then

through her electrical body. Her favorite place for meditation and creation

was on top of mountains that today we call the Himalayas. Her skin was transparent.

milkywhite, all the veins could be seen clearly. She had blue blood flowing

through. Her World was still. As She, the goddess Earth, created the seas, lakes,

rivers and oceans, the mist entered her pores and she had a terrible urge to

push. Through her third eye, millions of pearls were released, each of which

fumed into a different creature as it touched the Earth or the Waters.

When She opened her eyes, She realized

that it was lonely on the top and she was missing a partner. She envisioned

Man. But to create Him, She needed Tobacco, the sacred plant with which Magic

is performed. She descended from her great heights and searched for the plant.

When She finally found it, She rolled it into a Big Cigar, in order to create

smoke. En route back, She placed the Cigar in her Vagina, so as not to lose

it. This gave her such pleasure as She climbed back up, that She envisioned

Man with an organ just that shape. Together they would create offspring, in