Avatars

on the World Wide Web:

Marketing the "Descent"

Victoria Vesna

1995

was the year the Internet was opened to commercial use. After a reorganizationof

funding, the National Science Foundation (NSF) officially began planning

Internet2 - a collaborative efoort joining over 100 U.S. universities

- aimed at creating a network whose primary goal would be to facilitate research

and education missions of universities in the US. It is envisioned that this

network will be 100 to 1,000 times faster than the existing Internet. Applications

like tele-immersion and digital libraries will change the way people use computers

to learn, communicate and collaborate.[1]

Although the universities are taking lead in the initial development and research

of this network, this is a collaborative effort between federal government agencies,

private corporations and non-profit organizations. This means that it will probably

tae original Internet--first accessible and tested in research institutions,

then made publically available. Corporations such as IBM that have already

invested in this venture are most probably having long term plans for the commercial

potential of such a super fast network.

1995

was the year the Internet was opened to commercial use. After a reorganizationof

funding, the National Science Foundation (NSF) officially began planning

Internet2 - a collaborative efoort joining over 100 U.S. universities

- aimed at creating a network whose primary goal would be to facilitate research

and education missions of universities in the US. It is envisioned that this

network will be 100 to 1,000 times faster than the existing Internet. Applications

like tele-immersion and digital libraries will change the way people use computers

to learn, communicate and collaborate.[1]

Although the universities are taking lead in the initial development and research

of this network, this is a collaborative effort between federal government agencies,

private corporations and non-profit organizations. This means that it will probably

tae original Internet--first accessible and tested in research institutions,

then made publically available. Corporations such as IBM that have already

invested in this venture are most probably having long term plans for the commercial

potential of such a super fast network.

Opening

the Internet to the public had meant opening Pandora's box, and there was no

way anyone could even attempt to put a lid on the activities that were increasingly

taking place. Conceptualized as having only machines "talking" to

each other, its developers would have never guessed that this network of machines

would transform itself into a network of humans using the machines. Exponential

growth in the number of Internet users, the number of hosts connected to the

World Wide Web, and the number of companies establishing a Web presence has

created a gold rush mentality among firms and investors. This euphoria is largely

fueled by electronic commerce, and many companies are putting significant resources

towards figuring out the most effective ways of buying and selling everything

from groceries to clothing to movies over the Internet.

What

is particularly interesting about the commercialization of the net, however,

is that it is largely being driven by yesterday's anti-establishment hippies

and nerds, who have become overnight millionaires in the software industry.

Many of these new powerful personalities (with the exception of the most powerful

one) are bringing value systems influenced by eastern philosophies into the

market while collaborating with established corporate structures. Perhaps caught

between a dream and the mass market, it is interesting to look at how these

seemingly opposite worlds are taking form. This strange interplay, perhaps contradiction,

is best analyzed through our online selves in multi-user environments, also

known as "avatars"; a word that has now assumed a much narrower meaning

than its original theological source.

Defining

the "Avatar"

Defining

the "Avatar"

Before

delving into analyses of how projecmanifest on the Internet and what kind of

implications they may have on the future on our perception of the marketplace,

it may be useful to give an overview of the myriad definitions of the "avatar".

According

to the Dictionary of Hinduism (1977), "Avatara" means"descent",

especially of a god from heaven to earth. In the Puranas, an avatara

is an incarnation, and is distinguished from a divine emanation (vyuha), both

of which are associated with Visnu and Siva, but particularly the former. The

avatara concept is probably a development of the ancient myth that, by the creative

power of his Maya, a god can assume any format will, as did Indra. The avatara

concept in Hinduism is a very complex hierarchical system with many different

forms taking place.

Longman's

Dictionary (1985) also defines avatar as the incarnation of Vishnu, a Hindu

deity, and an embodiment of a concept or philosophy. The Oxford Dictionary,

on the other hand, tells us that avatar can mean descent of a deity to earth

in an incarnate form (i.e., as in "the fifth avatar appeared as a dwarf");

a manifestation or presentation to the world (i.e., the avatar of mathematics);

a display, a phase (1990). If you refer to the Webster's Dictionary,

it says that an avatar is a manifestation or embodiment of a person, concept

or philosophy; a variant phase or version of a continuing basic entity (1989).

And finally, the Random House Dictionary describes an avatar as: "An

embodiment or concrete manifestation as of a principle attitude, way of life,

or the like" (1995).

In

contemporary India, distinguished personalities may be called avatars, which

is a sign that even at the source, the original theological meaning has shifted

in popular culture. For instance, on the Web page of India Group, Partner Anil

Srivastava refers to himself as "Anil Srivastava, avatar of global

markets and emerging technologies, contemplates interactive media, networking,

and online services from the omphalos of the Silicon Valley.[2]

If

you ask anyone familiar with multi-user environments, the word simply means

an assumed identity in cyberspace. But, the source of the use of the word in

industry is a bit more difficult to identify. According to Peter Rothman,

founder of Avatar Software and Avatar Partners (and later DIVE

labs), "anyone claiming to know who used the word first, would be inventing

the facts."[3] Rothman and his

partner found the word in the dictionary in 1982, simply liking Webster's definition:

embodiment of a concept or a philosophy in a person. Appropriately, the debate

about this came up on the WELL discussion forum about the origin of the

word, in which Neal Stephenson claimed that he was first to use the term

in Snow Crash, but since the novel was not published until 1992, this

was not acknowledged. Generally, it is conceded that Randy Farmer and

Chip Morningstar's "Habitat" was the first to use this

term. They were inspired by the Hindu root of the word (Randall, 1995).

If

you ask anyone familiar with multi-user environments, the word simply means

an assumed identity in cyberspace. But, the source of the use of the word in

industry is a bit more difficult to identify. According to Peter Rothman,

founder of Avatar Software and Avatar Partners (and later DIVE

labs), "anyone claiming to know who used the word first, would be inventing

the facts."[3] Rothman and his

partner found the word in the dictionary in 1982, simply liking Webster's definition:

embodiment of a concept or a philosophy in a person. Appropriately, the debate

about this came up on the WELL discussion forum about the origin of the

word, in which Neal Stephenson claimed that he was first to use the term

in Snow Crash, but since the novel was not published until 1992, this

was not acknowledged. Generally, it is conceded that Randy Farmer and

Chip Morningstar's "Habitat" was the first to use this

term. They were inspired by the Hindu root of the word (Randall, 1995).

The

avatar name is apparently very popular these days. Numerous companies have registered

various versions of the name, usually by adding a word next to it. Some recent

examples are: Avatar Partners -- developing software for trading on the

net; Avatar Holdings -- a real estate developer of major resort, residential

and recreational communities; and Avatar Systems -- a moving company

specializing in corporate relocations, just to name a few. The commercial world

apparently has proprietary feelings towards the term. For example, at one point

Avatar Partners were being threatened with a lawsuit by the Avatar Financial

Associates who claimed to have been the first to have the name registered

and trademarked. And then there is the Avatar nine-day course on "contributing

to the creation of an enlightened planetary civilization." An enthusiastic

testimonial on the net by a devotee claims: "I enrolled in the Avatar course

in an attempt to alter behavior patterns that were interfering with the proper

conduct of my business. Avatar taught me how to easily ith the beliefs that

were causing my problems. . . . In addition, I found the Avatar experience to

be delightful and amazing. My life is fuller, more meaningful and pleasant since

I became an Avatar."[4]

Descent

of the Avatar

Descent

of the Avatar

The

idea of the avatar "coming down" from an unspecified source in one

of many possible manifestations connects well to the reverse hierarchy established

originally by the scientific community at the inception of what would become

the Internet: the client "uploads" to, and "downloads" from,

the server that resides above.

The

software industry's debate on avatars is really about object interactions passing

between a variety of servers in real-time. Talking about avatars personalizes

the discussion and brings up issues having to do with the nature of identity,

security, interpersonal relations, and societies of the Internet.

The

concept of an avatar can also be easily transferred to the many variants of

computer messages and presentations being transferred from the Web to "client"

computer screens. And, finally, all these concepts and hierarchies fit perfectly

with financial markets used to trading numbers. The idea of products or services

constructing themselves on a computer screen as a result of information "coming

down" from the Internet and the World Wide Web is a very attractive prospect

for entrepreneurs. There is a sense of power and control the owner of a server

has, once removed from the flesh market.

What

is particularly fascinating is how many are reading the mystical concepts of

the word avatar into various software applications. For instance, Peter Small

writes in the introduction of his online version of a book entitled Magical

Web Avatars:

What

is particularly fascinating is how many are reading the mystical concepts of

the word avatar into various software applications. For instance, Peter Small

writes in the introduction of his online version of a book entitled Magical

Web Avatars:

The mystical aspect implies

that the deity "Vishnu" has no specific form or shape before manifesting

as an avatar on earth. It is implicit that any physical appearance of an avatar

is merely a temporary form or phase from an infinite variety of possibilities--a

transient form from an indefinite, indefinable number of sources. It is the

capturing of this concept, which makes the word avatar ideal for the purpose

of describing the Web communication products which will be described in this

book" (Small, 1997).

Thus

product promotion is inextricably linked to mysticism and New Age values. This

is true for many softwares with mystically encoded connotations, and for the

marketing "gurus."

New

Ageism typically encompasses an eclectic mix of different religious elements,

claiming no allegiance to nationality or even specific Gods. Still, the strong

ideological character remains, linked very much to cultural processes and marketing

of products and ideas, and seems to be pervasive in the structuring of a significant

number of new high tech corporations. Certainly, the very choice of naming an

identity in networked spaces an"avatar" indicates this trend. The

avatar in cyberspace represents a strange interplay of left-wing utopianism

with right wing entrepreneurism, mixed up with esoteric spiritualism. New Age

religion operates in tandem with networking technologies and "organic"

corporate structures--the new "cool" companies that are emerging all

over the high tech industry map.

New

Ageism typically encompasses an eclectic mix of different religious elements,

claiming no allegiance to nationality or even specific Gods. Still, the strong

ideological character remains, linked very much to cultural processes and marketing

of products and ideas, and seems to be pervasive in the structuring of a significant

number of new high tech corporations. Certainly, the very choice of naming an

identity in networked spaces an"avatar" indicates this trend. The

avatar in cyberspace represents a strange interplay of left-wing utopianism

with right wing entrepreneurism, mixed up with esoteric spiritualism. New Age

religion operates in tandem with networking technologies and "organic"

corporate structures--the new "cool" companies that are emerging all

over the high tech industry map.

James

Hillman, a psychologist widely read by the corporate sector's elite, writes

in his influential best-seller, Kinds of Power: "Economics is the

only effective syncretistic cult remaining in the world today, our world's only

ecumenical faith. It provides the daily ritual, uniting Christian, Hindu, Mormon,

atheist, Buddhist, Sikh, Adventist, animist, evangelist, Muslim, Jew, fundamentalist

and New Ager in one common temple, admitting all alike . . ." (1995).

How

perfectthe Internet, then, to unite the multi-national corporations with their

customers regardless of nation, race or creed. The multi-user environment with

its dynamic design for instant communication and relations is the ideal space

for the creation of communities with their various interests and markets, commercial

or otherwise. Hence the World Wide Web, with its friendly graphical user interface--not

like its predecessors, the text-based virtual realities, only accessible by

the unix literati.

To

date, text based environments are still active with hundreds of thousands of

users, and provide useful research data for those planning commercial ventures

with graphical multi-user communities on the Web. Naturally, the graphical offspring

promise numbers projected into the hundreds of millions (Advertising Age, 1996).

There are over 500 MOOs (Turkle, 1995) in existence, with hundreds of thousands

of users who might easily make a transition from the text based environments

to more graphically designed spaces.

Hierarchies

of Multi-user Environments

Hierarchies

of Multi-user Environments

Examining

the hierarchy of MUDs and MOOs is helpful if we are to begin understanding the

evolving social structure of avatars in cyberspace.[5]

It is generally acknowledged that the Arch-Wizards are those who "own"

the MOO, and that those new to the environment are usually guests who progress

in their status as they become more active and experienced.

Most

MUDs and MOOs prefer to allow users to retain anonymity so as not to destroy

the online atmosphere by introduction of offline life. An exception to this

would be MIT's MediaMOO, where each character has a "character

name" and a "real_name."[6] Real names don't normally appear,

but can be seen with the @whois command. Only janitors (administrators of the

MOO) can set or change real names. Because the goal is to enhance community

amongst media researchers, you must provide a statement of your research interests

in order to be granted a character. Regardless of the specialized purpose of

the MOO, whether it is the most down-and-dirty fantasy dungeon and dragon MOO

or a MOO steeped in theory, people in charge of the code reside at the "top."

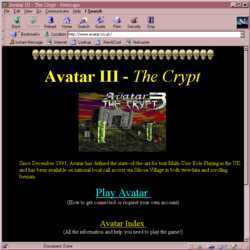

For

instance, Avatar III - The Crypt, is owned and run by a company in the

UK that specializes in games.[7] The Crypt is a beta site that presumably

will become commercial as soon as enough players visit it regularly. When you

first enter the site, you will get promotional materials--not at all enshrouded

in fantasy--about the company that produces the MOO. The avatar inhabitants

are--Shopkeepers, Moneychangers, Pawnbrokers, Pedlars, Town Guardsmen, Market

Traders and Citadel Traders. The Avatar classes are very different, and quests

are allocated to suit the skills of the different classes. The site's narrative

and hierarchy uncannily resembles the class system England is so familiar with.

For

instance, Avatar III - The Crypt, is owned and run by a company in the

UK that specializes in games.[7] The Crypt is a beta site that presumably

will become commercial as soon as enough players visit it regularly. When you

first enter the site, you will get promotional materials--not at all enshrouded

in fantasy--about the company that produces the MOO. The avatar inhabitants

are--Shopkeepers, Moneychangers, Pawnbrokers, Pedlars, Town Guardsmen, Market

Traders and Citadel Traders. The Avatar classes are very different, and quests

are allocated to suit the skills of the different classes. The site's narrative

and hierarchy uncannily resembles the class system England is so familiar with.

Rose,

a user of the five year old MOO since day one, has gained the status of a god.

She logs on daily to help newbies, and in this way gains points. One needs 1,000

experience points to move to the second level, and 1,024,000 to get to the twelfth

and highest level. Gods have the power to move uplevels to ensure that the lower

level gods can't force higher level gods to do things.[8]

Users

are encouraged to help those on lower levels, which not only teaches human relations,

but ensures a growing community. Thus the ones at the "top" assume

a role similar to those held be religious figures of the past. By providing

incentives they function as primary agents of socialization, and become more

powerful in the process.[9]

Particularly

interesting about Avatar III is that the role playing game is housed in a commercial

shopping site--Silicon Village. Thus, an entire community is formed around the

shopping site where users have the illusion of anonymity. The Arch-Avatars (owners),

on the other hand, can easily track all the personal information they may need

on users' likes and dislikes, newsgroup postings, favorite web sites, and navigational

habits. As soon as users enter a site, it bto learn where they go, what they

click on, their domain name, computer type, and general location. Personal information

is fast becoming a most precious commodity, and those who are positioned as

packagers and resellers of it will profit the most in the Information Age.

Particularly

interesting about Avatar III is that the role playing game is housed in a commercial

shopping site--Silicon Village. Thus, an entire community is formed around the

shopping site where users have the illusion of anonymity. The Arch-Avatars (owners),

on the other hand, can easily track all the personal information they may need

on users' likes and dislikes, newsgroup postings, favorite web sites, and navigational

habits. As soon as users enter a site, it bto learn where they go, what they

click on, their domain name, computer type, and general location. Personal information

is fast becoming a most precious commodity, and those who are positioned as

packagers and resellers of it will profit the most in the Information Age.

Descent

of the Graphical Avatar

Descent

of the Graphical Avatar

In

is truly awe-inspiring to survey how much progress industry has made in figuring

out ways to cash in on the potential markets of the World Wide Web. Star-featured

chat rooms sponsored by large companies, soap operas, online trading, and role

playing games seem to be the places where most success is promised. In other

words, any space that could potentially form large communities that will regularly

log on to communicate, exchange ideas and spend cybercash.

Avatar-filled

chat rooms seem to be where most entrepreneurs are placing their bets. By the

year 2000, chats are expected to generate 7.9 billion hours of online use, with

a resulting $1 billion in advertising revenue (New York Times, 1996).

But makers of virtual environments predict that scrolling text for chat rooms

will soon be replaced with 2-D and 3-D graphical environments, while marketers

are busily exploring ways to exploit new technology for advertising.

For

example, soap operas on the World Wide Web are seen as ideal environments for

marketing strategies involving advertisements built into the narratives.[10]

Moreover, in contrast with television, there are virtually no standards regulating

web-based advertising. Currently several cybersoaps allow advertisers the chance

to have their products integrated into the story line (Advertising Age,

1996).

For

example, soap operas on the World Wide Web are seen as ideal environments for

marketing strategies involving advertisements built into the narratives.[10]

Moreover, in contrast with television, there are virtually no standards regulating

web-based advertising. Currently several cybersoaps allow advertisers the chance

to have their products integrated into the story line (Advertising Age,

1996).

Meanwhile,

Rocket Science Games, a maker of interactive entertainment software,

and CyberCash, a company that handles payment transactions on the Internet,

are forming a partnership to develop a virtual video game arcade on the World

Wide Web. Scheduled for rollout later this year, Virtual Arcade will

feature interactive versions of classic video games. Users will reportedly be

able to modify the environments of the games, and they will pay as little as

25 cents to play each game. Payments will come out of an "electronic wallet"

that users could replenish by transferring money from their bank accounts (San

Francisco Chronicle, 1996).

Of

course none of these developments would be taking place with this kind of speed

if the WWW was a text-only environment. Although text-based MOOs and MUDs are

still very active communities, and there will probably always be a place for

them, the real gold-rush has started with the introduction of graphical user

interfaces. Graphical Multi-User Konversations ("GMUKs") are something

of a cross between a MOO and a chat room or channel. Rather than limiting users

to text-only communications, as in most virtual chat environments, GMUKs add

an audio-visual dimension that creates the illusion of movement and space.

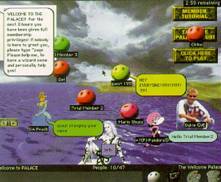

The

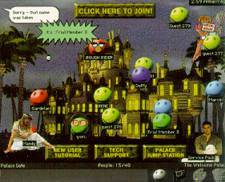

most popular GMUK, to date, is Time-Warner's The Palace, a client/server

program that creates a visual and spatial chat environment.[11]

Currently, there are many Palace sites located across the Internet, varying

widely in technical and artistic sophistication, as well as graphical themes.

Jim Bumgardner and Mark Jeffrey created and designed The Palace

at Time Warner's Palace Group. The software driving the environment was released

in November 1995. More than 300,000 client versions have been downloaded since

then, and over 1,000 commercial and private-hosted Palace communities have been

established. Major investors include Intel, Time Warner, Inc., and Softbank.

Companies like Capitol Records, Twentieth Century Fox, Fox Television, Sony

Pictures, MTV (Suller).

The

most popular GMUK, to date, is Time-Warner's The Palace, a client/server

program that creates a visual and spatial chat environment.[11]

Currently, there are many Palace sites located across the Internet, varying

widely in technical and artistic sophistication, as well as graphical themes.

Jim Bumgardner and Mark Jeffrey created and designed The Palace

at Time Warner's Palace Group. The software driving the environment was released

in November 1995. More than 300,000 client versions have been downloaded since

then, and over 1,000 commercial and private-hosted Palace communities have been

established. Major investors include Intel, Time Warner, Inc., and Softbank.

Companies like Capitol Records, Twentieth Century Fox, Fox Television, Sony

Pictures, MTV (Suller).

Time/Warner's

"avs," as Palace members affectionately call them, fall into two overall

categories. The first are the standard set of "smileys" that come

with the Palace program.

Time/Warner's

"avs," as Palace members affectionately call them, fall into two overall

categories. The first are the standard set of "smileys" that come

with the Palace program.  These

faces are available to all users, including unregistered "guests."

The standard avs are associated with newbies, the unregistered guests who are

considered a lower class of the Palace population. They have not paid the registration

fee, they do not belong to the Palace culture, and are limited to wearing only

the standard avs and props. They cannot create their own avatars, and are reduced

to wearing a smiley which identifies them as a newbie. Only after paying the

registration fee can the user unlock the prop-creating/editing feature of the

Palace software. At that point they are able to choose from Animal, Cartoon,

Celebrity, Evil, Real, Idiosyncratic, Positional, Power, Seductive or "Other"

avatars. The Palace is an excellent example of an environment in cyberspace

that is a combination of an established entertainment industry's approach to

pre-packaged programming for the public, reminiscent of developments such as

Disneyland or any planned community.

These

faces are available to all users, including unregistered "guests."

The standard avs are associated with newbies, the unregistered guests who are

considered a lower class of the Palace population. They have not paid the registration

fee, they do not belong to the Palace culture, and are limited to wearing only

the standard avs and props. They cannot create their own avatars, and are reduced

to wearing a smiley which identifies them as a newbie. Only after paying the

registration fee can the user unlock the prop-creating/editing feature of the

Palace software. At that point they are able to choose from Animal, Cartoon,

Celebrity, Evil, Real, Idiosyncratic, Positional, Power, Seductive or "Other"

avatars. The Palace is an excellent example of an environment in cyberspace

that is a combination of an established entertainment industry's approach to

pre-packaged programming for the public, reminiscent of developments such as

Disneyland or any planned community.

Earth

to Avatar

Earth

to Avatar

The

biggest problem faced by industry in developing multi-user environments for

avatars is the fact that people can assume many identities and are still quite

difficult to track down. This is largely due to the lack of a universal standard

allowing the avatars to move from one virtual world to another. There are a

number of avatars currently on the Web--VRML, 2D, text, Voxel-drawn ones, and

Virtual Humans (which refers to the group set up by VR News to exchange

information about the development of autonomous agents that look like human

beings).

Buying

patterns, monetary exchange, security, and authentication must be maintained

in the avatar in order for a market to be fully developed. Using standardized

avatars can help in using Internet search engines for avatars and avatar properties.

Finally, avatar companies have become common--they can price their avatars at

a lower cost, make them available to more people and guarantee broader applicability.

In

October '96, at the Earth to Avatar Conference in San Francisco, architects

of 3D graphical interfaces on the web met to discuss the lack of avatar standards.

When former Apple Computer Chairman John Sculley gave his analysis

of the future of cyberspace at the conference, he said that once the technology

is shown to work and standards are agreed, the big league players will move

into cyberspace. As avatars become members of self-organizing groups, Sculley

sees them as "a driving force shaping the economics of this industry"

(Wilcox).

In

October '96, at the Earth to Avatar Conference in San Francisco, architects

of 3D graphical interfaces on the web met to discuss the lack of avatar standards.

When former Apple Computer Chairman John Sculley gave his analysis

of the future of cyberspace at the conference, he said that once the technology

is shown to work and standards are agreed, the big league players will move

into cyberspace. As avatars become members of self-organizing groups, Sculley

sees them as "a driving force shaping the economics of this industry"

(Wilcox).

Universal

Avatar Standards group stated that their core aim is to focus on the nature

of avatars with regard to such issues as gender representation, ID authentication,

personal expression versus social constraints, avatar versus world scale, and

the communication of emotion. Maclen Marvit, teleologist of Worlds

in San Francisco, provides this overview of UA's approach:

We are at a point in our

industry where lots of companies are doing innovative things, both technically

and artistically. The goal of UA is to allow users to move as freely as possible

between the technologies and find the best experiences in each, while maintaining

a consistent identity. So if Bernie moves from one "world" [developed

using] one technology to another "world" in another technology,

he can maintain his avatar's representation, his Internet phone number and

his proof of identity" (Wilcox).

The

proposal provides an architecture for managing thousands of geographically distant

users simultaneously, with interactive behaviors, voice, 3-D graphics and localized

audio. It uses a powerful concept known as "regions," which allows

for multiple contiguous worlds, accelerated 3-D graphics, and efficient server/client

communications. The avatar standards issue is crucial to the success of VRML

as a commercially viable language. Until there is some common definition of

an avatar, and universality of movement between spaces on the Internet, it seems

unlikely that any VRML company can hope to make serious money.

The

proposal discusses creation of a link to a user profile, coded in HTML and containing

data the user wishes to be known either about his fantasy identity or a true

one. Proofs of identity Vendor-specific extensions and user's history. A history

could be with reference to games, for example, wizard status in a Role Playing

Game (RPG), or it could hold marketing information about purchases made by credit

card.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The

Internet as it exists today is one large market testing ground--a living laboratory

of sorts. It is clear that most companies are moving in the direction of developing

multi-user communities with standardized avatars. Because standardization renders

identity in fixed and accountable form, the connection between the users' physical

self and bank accounts will not be confused. What will be confused by design,

however, is the power status of the avatar--i.e., who is really the "user"

and who the "used." In a paradox of power relations, the corporations

practice their accustomed method of top-down hierarchy to lift lowly users into

the avatar's "god sphere." Be as gods, the hidden god thus decrees;

and it is technology and its invisible priests (those who control the servers)

who are the real avatar of the god sphere. When the Internet2 "descends,"

and when avatars are standardized and cybercash perfected, we will be looking

out upon a world that we can't even imagine, because it has been imagined for

us.

NOTES

Special thanks to Alan Liu

and Robert Nideffer for their suggestions during the revision of this essay.

1.

Internet2--also known as I2--is a collaborative effort joining over 100 U.S.

universities. See http://www.internet2.edu

(Back)

2.

Anil

Srivastava - - http://www.indonet.com/AnilSrivastava.html (Back)

3.

I interviewed Peter Rothman on December 31, 1996, at MetaTools INC. in Carpinteria.

His company, DIVE, was acquired by MetaTools, and he is currently the director

of Research & Development. (Back)

4.

William L. Owens, Wisconsin, USA http://www.epcnet.com/avatar/index.html

(Back)

5.

MOO, technically, means MUD-Object Oriented. And MUD is a Multiple-User Dungeon

(or Dimension. MUDs started as interactive adventure games similar to Dungeons

and Dragons for the computer--but a version that participants could play over

the Internet. Since those days, the use of MUDs have expanded to other sorts

of games and to more social uses. The object-orientation of MOOs puts more of

the programming focus on the "objects" that are in the MOO. Some of

the most significant research done to date on MUDs and MOOs has taken place

at Xerox Parc, University of Virginia and the MIT media lab. At Xerox Parc,

Curtis Pavel established LambdaMOO and wrote on the social phenomena of Text-Based

virtual realities (1992). (Back)

6.

MediaMOO, http://www.cc.gatech.edu/fac/Amy.Bruckman/MediaMOO/

To connect to MediaMOO from a UNIX host telenet: mediamoo.cc.gatech.edu 8888

- From a VMS host, type: telnet mediamoo.cc.gatech.edu /port=8888(Back)

7.

Avatar III - the Crypt - http://www.avatar.co.uk/

(Back)

8.

I interviewed Rose on May 29, 1997. In RL (real life), she works in a social

security office. (Back)

9.

An example of a code

of conduct in a online game, original from: http://games.world.co.uk/code_of_conduct.html

(Back)

10.

Online soaps include:

- The

Spot: (full site at http://www.thespot.com)

- Ferndale - No longer

in existence

- Techno 3 - No longer

in existence

- The East Village - No

longer in existence

(Back)

11.

The Palace Home Page -- http://www.thepalace.com

(Back)

REFERENCES

Dunn, A., "Think of

Your Soul as a Market Niche," New York Times Cybertimes September

11, 1996.

Cleland, K., "Chat

Gives Marketers Something to Talk About," Advertising Age August

5, 1996.

Curtis, P. (1992), "Mudding:

Social Phenomena in Text-based Virtual realities," unpublished, available

via anonymous FTP: ftp://parcftp.xerox.com/pub/MOO/papers/DIAC92.txt

Dillstone, F.W., (1951)

The Structure of the Divine Society, Lutterworth Press.

Donovan, L., "Secret

Identities (Secure Electronic Signatures Would Aid Internet Commerce),"

Financial Times 2/6/96.

Einstein, D., "Virtual

Arcade Games Play the classics on the Internet," San Francisco Chronicle

February 13, 1996 p. C3.

Hendrickson, R. (1987),

Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins, New York: Facts on File.

Levere, J., "Advertising:

With Soap Operas on Web, What's Next?," The New York Times March

11, 1996.

Longman Dictionary,

(1985) Harlow [Essex] : Longman.

Oxford Dictionary,

(1990) New York : Oxford University Press.

Randall, F. et al. "From

Habitat to Global Cyberspace," unpublished, available via the World

Wide Web: http://www.communities.com/paper/hab2cybr.html

Random House Dictionary,

(1994) New York: Random House.

Riedman, P., "Avatars

Build Character on 3-D Chat Sites," Advertising Age September 1996.

Small, P., "Magical

Web Avatars: The Sorcery of Biotelemorphic Cells" http://192.41.36.58/avatars/Index.htm

Stutley, M. (1977) Dictionary

of Hinduism, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Stephenson, N., (1992) Snow

Crash, New York: Bantam Books.

Suler, J. (Nov. 1996). "The

Psychology of Cyberspace." World Wide Web, http://www1.rider.edu/~suler/psycyber

Turkle, S, (1984) The

Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Turkle, S, (1995), Life

on the Screen, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Webster's New dictionary,

(1991) Cleveland : Webster's New World.

Wilcox, S. (1996), "Bringing

'Behaviors' to VRML: Making Sense of the Avatar debate," Netscape

World, January 1997 http://www.netscapeworld.com/netscapeworld/nw-01-1997/nw-01-avatar.html

1995

was the year the Internet was opened to commercial use. After a reorganizationof

funding, the National Science Foundation (NSF) officially began planning

Internet2 - a collaborative efoort joining over 100 U.S. universities

- aimed at creating a network whose primary goal would be to facilitate research

and education missions of universities in the US. It is envisioned that this

network will be 100 to 1,000 times faster than the existing Internet. Applications

like tele-immersion and digital libraries will change the way people use computers

to learn, communicate and collaborate.[1]

Although the universities are taking lead in the initial development and research

of this network, this is a collaborative effort between federal government agencies,

private corporations and non-profit organizations. This means that it will probably

tae original Internet--first accessible and tested in research institutions,

then made publically available. Corporations such as IBM that have already

invested in this venture are most probably having long term plans for the commercial

potential of such a super fast network.

![]() If

you ask anyone familiar with multi-user environments, the word simply means

an assumed identity in cyberspace. But, the source of the use of the word in

industry is a bit more difficult to identify. According to Peter Rothman,

founder of Avatar Software and Avatar Partners (and later DIVE

labs), "anyone claiming to know who used the word first, would be inventing

the facts."[3] Rothman and his

partner found the word in the dictionary in 1982, simply liking Webster's definition:

embodiment of a concept or a philosophy in a person. Appropriately, the debate

about this came up on the WELL discussion forum about the origin of the

word, in which Neal Stephenson claimed that he was first to use the term

in Snow Crash, but since the novel was not published until 1992, this

was not acknowledged. Generally, it is conceded that Randy Farmer and

Chip Morningstar's "Habitat" was the first to use this

term. They were inspired by the Hindu root of the word (Randall, 1995).

If

you ask anyone familiar with multi-user environments, the word simply means

an assumed identity in cyberspace. But, the source of the use of the word in

industry is a bit more difficult to identify. According to Peter Rothman,

founder of Avatar Software and Avatar Partners (and later DIVE

labs), "anyone claiming to know who used the word first, would be inventing

the facts."[3] Rothman and his

partner found the word in the dictionary in 1982, simply liking Webster's definition:

embodiment of a concept or a philosophy in a person. Appropriately, the debate

about this came up on the WELL discussion forum about the origin of the

word, in which Neal Stephenson claimed that he was first to use the term

in Snow Crash, but since the novel was not published until 1992, this

was not acknowledged. Generally, it is conceded that Randy Farmer and

Chip Morningstar's "Habitat" was the first to use this

term. They were inspired by the Hindu root of the word (Randall, 1995).![]() What

is particularly fascinating is how many are reading the mystical concepts of

the word avatar into various software applications. For instance, Peter Small

writes in the introduction of his online version of a book entitled Magical

Web Avatars:

What

is particularly fascinating is how many are reading the mystical concepts of

the word avatar into various software applications. For instance, Peter Small

writes in the introduction of his online version of a book entitled Magical

Web Avatars:![]() New

Ageism typically encompasses an eclectic mix of different religious elements,

claiming no allegiance to nationality or even specific Gods. Still, the strong

ideological character remains, linked very much to cultural processes and marketing

of products and ideas, and seems to be pervasive in the structuring of a significant

number of new high tech corporations. Certainly, the very choice of naming an

identity in networked spaces an"avatar" indicates this trend. The

avatar in cyberspace represents a strange interplay of left-wing utopianism

with right wing entrepreneurism, mixed up with esoteric spiritualism. New Age

religion operates in tandem with networking technologies and "organic"

corporate structures--the new "cool" companies that are emerging all

over the high tech industry map.

New

Ageism typically encompasses an eclectic mix of different religious elements,

claiming no allegiance to nationality or even specific Gods. Still, the strong

ideological character remains, linked very much to cultural processes and marketing

of products and ideas, and seems to be pervasive in the structuring of a significant

number of new high tech corporations. Certainly, the very choice of naming an

identity in networked spaces an"avatar" indicates this trend. The

avatar in cyberspace represents a strange interplay of left-wing utopianism

with right wing entrepreneurism, mixed up with esoteric spiritualism. New Age

religion operates in tandem with networking technologies and "organic"

corporate structures--the new "cool" companies that are emerging all

over the high tech industry map.![]() For

instance, Avatar III - The Crypt, is owned and run by a company in the

UK that specializes in games.[7] The Crypt is a beta site that presumably

will become commercial as soon as enough players visit it regularly. When you

first enter the site, you will get promotional materials--not at all enshrouded

in fantasy--about the company that produces the MOO. The avatar inhabitants

are--Shopkeepers, Moneychangers, Pawnbrokers, Pedlars, Town Guardsmen, Market

Traders and Citadel Traders. The Avatar classes are very different, and quests

are allocated to suit the skills of the different classes. The site's narrative

and hierarchy uncannily resembles the class system England is so familiar with.

For

instance, Avatar III - The Crypt, is owned and run by a company in the

UK that specializes in games.[7] The Crypt is a beta site that presumably

will become commercial as soon as enough players visit it regularly. When you

first enter the site, you will get promotional materials--not at all enshrouded

in fantasy--about the company that produces the MOO. The avatar inhabitants

are--Shopkeepers, Moneychangers, Pawnbrokers, Pedlars, Town Guardsmen, Market

Traders and Citadel Traders. The Avatar classes are very different, and quests

are allocated to suit the skills of the different classes. The site's narrative

and hierarchy uncannily resembles the class system England is so familiar with.![]() Particularly

interesting about Avatar III is that the role playing game is housed in a commercial

shopping site--Silicon Village. Thus, an entire community is formed around the

shopping site where users have the illusion of anonymity. The Arch-Avatars (owners),

on the other hand, can easily track all the personal information they may need

on users' likes and dislikes, newsgroup postings, favorite web sites, and navigational

habits. As soon as users enter a site, it bto learn where they go, what they

click on, their domain name, computer type, and general location. Personal information

is fast becoming a most precious commodity, and those who are positioned as

packagers and resellers of it will profit the most in the Information Age.

Particularly

interesting about Avatar III is that the role playing game is housed in a commercial

shopping site--Silicon Village. Thus, an entire community is formed around the

shopping site where users have the illusion of anonymity. The Arch-Avatars (owners),

on the other hand, can easily track all the personal information they may need

on users' likes and dislikes, newsgroup postings, favorite web sites, and navigational

habits. As soon as users enter a site, it bto learn where they go, what they

click on, their domain name, computer type, and general location. Personal information

is fast becoming a most precious commodity, and those who are positioned as

packagers and resellers of it will profit the most in the Information Age.![]() For

example, soap operas on the World Wide Web are seen as ideal environments for

marketing strategies involving advertisements built into the narratives.[10]

Moreover, in contrast with television, there are virtually no standards regulating

web-based advertising. Currently several cybersoaps allow advertisers the chance

to have their products integrated into the story line (Advertising Age,

1996).

For

example, soap operas on the World Wide Web are seen as ideal environments for

marketing strategies involving advertisements built into the narratives.[10]

Moreover, in contrast with television, there are virtually no standards regulating

web-based advertising. Currently several cybersoaps allow advertisers the chance

to have their products integrated into the story line (Advertising Age,

1996).![]() The

most popular GMUK, to date, is Time-Warner's The Palace, a client/server

program that creates a visual and spatial chat environment.[11]

Currently, there are many Palace sites located across the Internet, varying

widely in technical and artistic sophistication, as well as graphical themes.

Jim Bumgardner and Mark Jeffrey created and designed The Palace

at Time Warner's Palace Group. The software driving the environment was released

in November 1995. More than 300,000 client versions have been downloaded since

then, and over 1,000 commercial and private-hosted Palace communities have been

established. Major investors include Intel, Time Warner, Inc., and Softbank.

Companies like Capitol Records, Twentieth Century Fox, Fox Television, Sony

Pictures, MTV (Suller).

The

most popular GMUK, to date, is Time-Warner's The Palace, a client/server

program that creates a visual and spatial chat environment.[11]

Currently, there are many Palace sites located across the Internet, varying

widely in technical and artistic sophistication, as well as graphical themes.

Jim Bumgardner and Mark Jeffrey created and designed The Palace

at Time Warner's Palace Group. The software driving the environment was released

in November 1995. More than 300,000 client versions have been downloaded since

then, and over 1,000 commercial and private-hosted Palace communities have been

established. Major investors include Intel, Time Warner, Inc., and Softbank.

Companies like Capitol Records, Twentieth Century Fox, Fox Television, Sony

Pictures, MTV (Suller).![]()

![]() These

faces are available to all users, including unregistered "guests."

The standard avs are associated with newbies, the unregistered guests who are

considered a lower class of the Palace population. They have not paid the registration

fee, they do not belong to the Palace culture, and are limited to wearing only

the standard avs and props. They cannot create their own avatars, and are reduced

to wearing a smiley which identifies them as a newbie. Only after paying the

registration fee can the user unlock the prop-creating/editing feature of the

Palace software. At that point they are able to choose from Animal, Cartoon,

Celebrity, Evil, Real, Idiosyncratic, Positional, Power, Seductive or "Other"

avatars. The Palace is an excellent example of an environment in cyberspace

that is a combination of an established entertainment industry's approach to

pre-packaged programming for the public, reminiscent of developments such as

Disneyland or any planned community.

These

faces are available to all users, including unregistered "guests."

The standard avs are associated with newbies, the unregistered guests who are

considered a lower class of the Palace population. They have not paid the registration

fee, they do not belong to the Palace culture, and are limited to wearing only

the standard avs and props. They cannot create their own avatars, and are reduced

to wearing a smiley which identifies them as a newbie. Only after paying the

registration fee can the user unlock the prop-creating/editing feature of the

Palace software. At that point they are able to choose from Animal, Cartoon,

Celebrity, Evil, Real, Idiosyncratic, Positional, Power, Seductive or "Other"

avatars. The Palace is an excellent example of an environment in cyberspace

that is a combination of an established entertainment industry's approach to

pre-packaged programming for the public, reminiscent of developments such as

Disneyland or any planned community.![]() In

October '96, at the Earth to Avatar Conference in San Francisco, architects

of 3D graphical interfaces on the web met to discuss the lack of avatar standards.

When former Apple Computer Chairman John Sculley gave his analysis

of the future of cyberspace at the conference, he said that once the technology

is shown to work and standards are agreed, the big league players will move

into cyberspace. As avatars become members of self-organizing groups, Sculley

sees them as "a driving force shaping the economics of this industry"

(Wilcox).

In

October '96, at the Earth to Avatar Conference in San Francisco, architects

of 3D graphical interfaces on the web met to discuss the lack of avatar standards.

When former Apple Computer Chairman John Sculley gave his analysis

of the future of cyberspace at the conference, he said that once the technology

is shown to work and standards are agreed, the big league players will move

into cyberspace. As avatars become members of self-organizing groups, Sculley

sees them as "a driving force shaping the economics of this industry"

(Wilcox).